Deputy Mayor Judith Thomas, historian DeeDee Davis and archaeologist Ryan Peterson look at archival records.

Jill Sheridan / WFYIAn excavation project is underway on the site of Indianapolis’s first cemetery.

The one-acre site is just a small piece of a property along the White River, where Indy Eleven had planned to build a new soccer stadium.

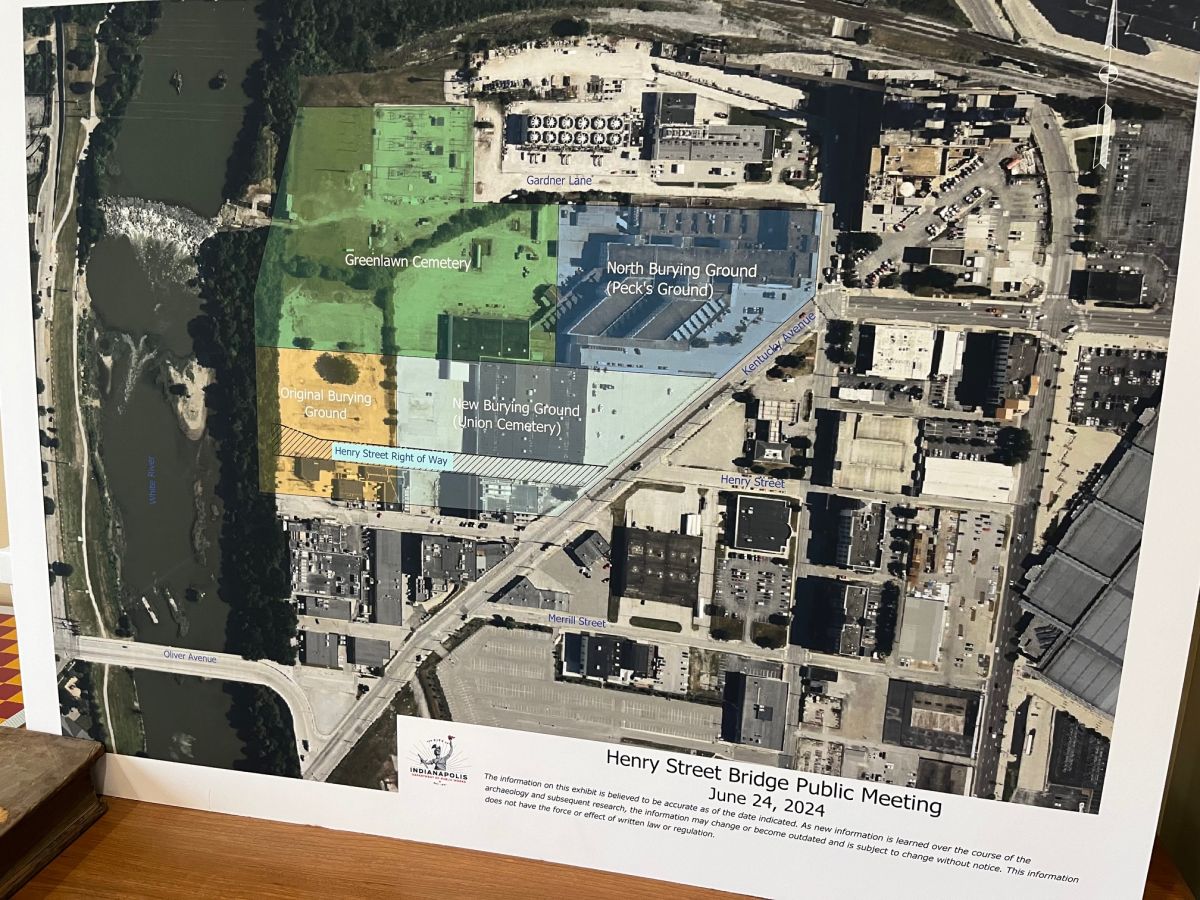

The land is also part of a downtown redevelopment area that includes White River State Park expansion and new global headquarters for animal health company Elanco. The site will anchor the new Henry Street bridge that will connect neighborhoods, expand the cultural trail and honor stories of those buried in Indianapolis’s first public burial grounds.

In a now abandoned courtroom in the City-County Building, piles of books, ledgers and artifacts are stacked on tables and in shelves. Among the archives are maps and photographs that give clues about the city’s first cemetery. Presiding over this collection is Jordan Ryan, the city’s archivist.

Ryan is part of a city-led project that digs into the history of what is commonly-called Greenlawn Cemetery.

“Whether you were black or white, rich or poor, old or young, like you lived your life here. You died here, and you were probably buried here,” Ryan said, “and there are so many narratives to unerase.”

Those stories are at the core of the project’s goal to conduct this project with integrity, respect and meaning. Even though the excavation focuses on only one acre of the larger 20-acre cemetery site. Ryan said that’s still significant.

“So how do we humanize this and tell 100 500 1000 stories?” Ryan said, “This is truly a gift for the city.”

Through the decades, documentation of the cemetery has been incomplete and chaotic. It wasn’t until Indy Eleven made a bid to develop the site – and the city made plans to construct a new bridge on the site — that residents elevated the historical significance of the cemetery -– including that it is likely the resting place of Indianapolis’s first Black citizens.

Deputy Mayor of Neighborhoods Judith Thomas has worked closely with a community advisory group and historians to inform discovery.

“We're about to build a new Indianapolis, in a way, but we need to definitely honor the past,” Thomas said.

After the city pulled support for the Indy Eleven stadium, in hopes of a major league team, the archeological project became more of a priority. Many important historical records are unavailable in the city archives.

“Thank God for the AME churches and the black churches that kept record of who was buried where and who these people were. They were landowners. They were people that made a big impact in their, in their city, and that their descendants are still here,” Thomas said.

The first pioneer graves were dug in the early 1820’s. Thousands were buried in the larger burial ground, that included four cemeteries, before the land was closed to burials in the 1890’s. Some were moved to Crown Hill and other local cemeteries over the decades that followed. It’s difficult to determine exactly how many people were buried there and how many may have been left behind.

“We have every archival obstacle you can think of. We don't have the original deed or plot for that original burying ground. We don't have sexton records, so that cemetery caretaker, typically, they have a ledger where they're listing all of the individuals who are buried by date, by location. We don't have that luxury,” Ryan said. “So we're dealing with a lot of archival mysteries that we have to uncover, on top of the topographical, financial, political obstacles, and we're dealing with a lot here.”

This is the city’s first attempt to document and preserve the history of others buried at the city cemetery. The city contracted archeological company Stantec for the dig work. Lead consultant Ryan Peterson said they start with an excavator, slowly digging through the soil layers.

“So we can see different soil texture changes as well as changes in the colors that show us where those graves are located,” Peterson said.

They’ve discovered more than 170 grave shafts so far. And they track numbers and findings on a new publicly available website, to maximize transparency. When a new shaft is found, the next step starts.

“Work in teams of two, and then, as we remove soil from the grave context that gets screened through very fine mesh to make sure that we're recovering absolutely everything possible,” Peterson said.

Many historians and community members that were initially worried about the excavation project are pleased with the city’s current work. Local historian DeeDee Davis has studied the site for years. She said the lack of public awareness about the city’s first cemetery has hindered historians.

“Up until this point in time. You know, when I started doing research on the site, the only people that really knew anything about Greenlawn were people that worked at Diamond Chain, and it's always like ghost stories and stuff like that,” Davis said.

Diamond Chain was a bike chain manufacturing company built in the 1920’s and stood on the riverfront site for a century. Davis has studied records of those moved to Crown Hill and other local cemeteries when it was built, so when recent excavation uncovered a footstone with the initials M.E.B., Davis was prepared.

“You know, we see this name on the stone, and it's already in my head. I mean, this is a name that I've already researched,” Davis said. M.E.B. are the initials of a person who was relocated. They could be related.

The Diamond Chain factory was torn down last year to make way for the Indy Eleven stadium. The larger 20 acre-site was cleared but sits empty now, fenced off from the current excavation project.

The records pose more questions for archeologists and historians concerned about the larger site. For example, Davis said that as people were moved and the cemetery grew, gravesites may have been built on top of one another.

“There's not much evidence out of it that you could figure that out,” Davis said, “So it's a big mess that I don't envy for these guys to have to figure out, but that's what the records show.”

The future of the Indy Eleven site that covers most of the city cemetery area is unknown for now.

The excavation is scheduled to be completed this year. The city plans to commemorate the cemetery on the redeveloped site with plaques and other information about the people buried there.

Contact WFYI Managing City Editor Jill Sheridan at jsheridan@wfyi.org.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.