Twenty-year-old Luis Vazquez lost his job constructing barricades in March, right before COVID-19 was officially declared a pandemic. Like tens of thousand of Hoosiers since then, he considered applying for unemployment insurance.

“My mom was actually the one who said, you should try for unemployment,” Vazquez said. “I said, there's no way I'll get it. And she's like, well just try. See what happens.”

So Vazquez tried. He was denied at first, but then he got a letter from the state saying, maybe try applying for this new program Congress created called Pandemic Unemployment Assistance. He followed the state’s instructions and within weeks he started getting money.

“I just applied, answered it to the best of my ability, got accepted, cool,” he said.

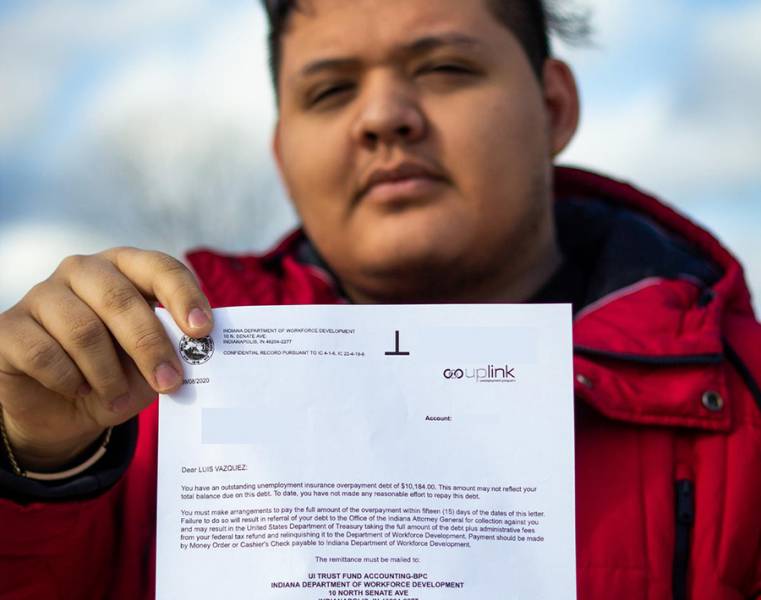

But suddenly the payments stopped. Shortly after, Vazquez started getting letters from the Department of Workforce Development. They said he owed them back more than $10,000 – and if he didn’t pay it, they would take it from taxes or even garnish future wages.

“At least the way I perceived it, and my parents perceived it, they're asking for that money back like now – in hand, now, everything back,” he said.

Vazquez was terrified. He didn’t have that kind of money. What’s more, lawyers describe the DWD letters threatening to collect money right away as "aggressive and improper" – and maybe not even allowable under state law.

Kristin Hoffman of Indiana Legal Services says, based on her interpretation, Indiana state law is supposed to keep collections at bay until unemployed workers can appeal their case in front of a judge. That’s not always happening.

“So they are commencing recovery before that period of time has passed and that is impermissible under Indiana law,” she said.

In late September, Indiana reported to the U.S. Department of Labor it may have overpaid around 34,000 claims on regular unemployment insurance alone. Thousands more cases were listed as overpaid on newer federal unemployment programs, too. That means scores of Hoosiers are receiving collection notices like Vazquez.

DWD declined requests for interviews, but sent a written statement. It said the department is working to address Indiana Legal Services’ concerns as is “appropriate and feasible.”

It notes the department updated the first overpayment letters to include information about how to get overpayments waived. It also halted garnishing wages during the pandemic and reduced subtractions from current benefits to no more than $10 per week.

Hoffman says DWD told her weeks ago it hasn’t made more changes because it requires attention from IT staff that they can’t spare right now.

“We’re applauding those changes and are very appreciative of that progress, but there is more to do and the client experience underscores the importance of directing more funding, more resources, to DWD,” Hoffman said.

In the meantime, she advises people to appeal their cases quickly and keep filing for benefits each week while they wait for a hearing.

In the end, Vazquez says he was extremely fortunate. A judge resolved his case without him having to pay anything. But now, Vazquez says no matter what, he’d never apply for unemployment benefits again.

“Never again,” Vazquez said. “I don't care how easy it is. I'm never touching that again.”

Hoffman says scaring people away – especially when people thought they were doing everything right – is a harmful side effect of these immediate debt collection policies.

“The system was designed to be a safety net,” she said. “Claimants should not feel bullied to the point where they don't feel like they can use that when they need to in the future.”

Michele Evermore, a researcher at the National Employment Law Project, says most states either have, or will soon, see spikes in overpayments too. But she says many are handling those claims with a much less aggressive approach and are trying to find ways to forgive broad swaths of overpayments.

“A lot of other states recognize the value in making sure there isn’t increased economic pain in their state right now,” Evermore said. “When you claw all that money back, that doesn’t just hurt the individual. It’s hard on the community and the economy as well.”

One final note: The latest relief bill from Congress gives states the ability to forgive overpayments on federal unemployment benefits, something they couldn’t do before. But as Indiana is still rolling out those changes, it’s hard to say what that will mean just yet.

Contact reporter Justin at jhicks@wvpe.org or follow him on Twitter at @Hicks_JustinM.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.