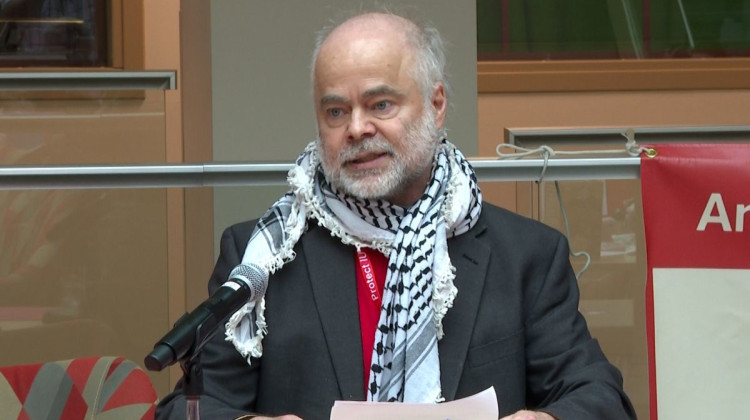

Fifth grade teacher Eddie Rangel, who is half Mexican, recently realized that he needed to accept his own culture, which has inspired his other students to do the same. Rangel is trying to take a proactive approach to diversity in his classroom as he shares his excitement while helping students solve a math problem as they simplify fractions at IPS Key Learning Community School. Photo by Matt Detrich/The Indianapolis Star

The district is embarking on an effort to overhaul its services for children who are learning to speak English

Eddie Rangel wasn’t about to let six-year-old Maite duck her real name, although she cowered with embarrassment at his Mexican pronunciation of her name as “My-tay.”

The teacher, who is half Mexican, understood that Maite wanted to Americanize her name to fit in with her peers, but he wouldn’t let up.

Then, suddenly, Maite turned the question back on him: Could she call him by his real name? Mr. “Ron-hel?”

The question forever changed Rangel’s Key Learning Community classroom: All of his students now use the Mexican pronunciation of his name, he’s made his curriculum more culturally sensitive, and he’s making a better effort to communicate with his students’ Spanish-speaking parents.

Now, Indianapolis Public Schools is embarking on its own rethinking of the way it assists students who are still learning English. The district plans to train educators to use better strategies in the classroom to help English learners and to improve communication with and support for its growing population of immigrant families. Efforts are also underway to increase the diversity of IPS’ teaching staff.

Jessica Feeser, IPS’ new director of education for English language learners, said the changes are needed to reverse a troubling trend: The students are falling behind their peers.

Just 43 percent of the district’s English learners passed ISTEP last year — 10 percentage points behind than their peers. The graduation rate for English language learners last year was more than 7 percentage points worse than the district’s 71 percent average. And 15 of the 25 IPS schools with the largest gains in enrollment of English learners since 2006 earned a grade of C or lower from the state last year.

“We can’t wait until tomorrow or the next day to make things happen,” Feeser said. “They’re working twice as hard. That means as teachers we need to work twice as hard.”

But the sharp growth of English language learners at IPS — enrollment has nearly tripled since 2001 to almost 5,000 students this year — has led to challenges that district officials say are hard to overcome.

Few teachers have the kinds of ethnic connections with students that Rangel does, and parents say the district’s communication with non-English-speaking parents is poor. And until now, only English as a second language teachers have explicit training and charge to serve students who are learning English.

Better training for better teaching

That will soon change, Feeser said, and many more teachers will know how to tailor their instruction for students who are learning English.

“Coloring worksheets at the high school level are not going to get our children prepared for college and careers,” Feeser said.

There’s nothing mean-spirited about the way things have worked at IPS, Feeser said. But helping kids learn English was seen as somebody else’s responsibility. Teachers didn’t feel they had the tools to meet the students’ needs.

This summer, IPS will launch its first district-wide effort to train general education teachers in strategies to specifically reach English learners. It’s starting with two high schools — Northwest and George Washington — where teachers will learn about “sheltered” instruction in which they cover all of the same Indiana standards but use different lessons for language learners. For example, a sheltered lesson on comparing and contrasting text might use a city bus route instead of Shakespeare.

Javier Barrera, a 2003 Northwest High School graduate and advocate for undocumented youth who came to the U.S. as a teen from Mexico, said the new techniques are desperately needed.

“They assumed that because we were immigrant students and we were not English speakers that it wasn’t even worth it to invest time and resources into us,” Barrera said of his experience in IPS.

Parents say communication is lacking

When Rangel realized the key to helping Logan, a boy learning English, succeed in his class was a frank conversation with his mother, he was determined that their language barrier not hold them back.

“He’s got a bright future,” said Rangel, a Teach Plus fellow who came to IPS through Teach For America. “He’s getting a B and he’s an A student.”

Slowly, they began to work together to keep track of Logan’s needs despite his limited Spanish and her limited English. Recently, she came in for a parent-teacher conference without a translator.

“I had my broken Spanish and she had her broken English and we met in the middle,” Rangel said. “It was the truest form of a dialogue and we were helping each other.”

But some parents say that level of outreach is rare in IPS.

School 88 parent Evelyn Barreuto, a Spanish speaker, said she has struggled to track the progress of her three children — Isaac, Benjamin and Belen. Through an interpreter, she said she is concerned about the lack of resources for Spanish-speaking parents.

Barreuto said there’s little to no translation help. She mainly relies on her children, who are fluent in English, or an interpreter from Stand for Children, a group that advocates for change in IPS, to keep her informed.

“I can understand a little English, not a lot, I know, but I have never let that stop me from communicating with teachers and the principal,” said Barreuto.

School board President Diane Arnold said the district needs to do better.

“You can’t have people be part of the process if they can’t fully participate,” Arnold said.

Feeser said she wants to increase efforts to connect with IPS’s non-English speaking community.

In January she invited ESL teachers, translators, community centers, faith-based groups, charter schools, immigration attorneys and local businesses together with the goal of trying to connect IPS families to resources they might not have realized existed.

“I see our schools as the heart and soul of the community,” Feeser said. “If students are in an emotionally happy place — they’ve got their basic health care needs met, they’ve got full bellies and a warm place to sleep — we know they’re going to come back to school and be ready to learn.”

Trying to recruit more diverse educators

The lack of diversity in the district’s workforce has become more glaring as its student population changes.

More than 23 percent of IPS students are Hispanic, but only about 2 percent of the district’s teachers are, according to the Indiana Department of Education.

And the district had just a single Latino school administrator — until it laid him off last year.

The decision to lay off Joel Muñoz, an assistant principal at George Washington High School, did not go over well in the Hispanic community. He had just been a finalist for a statewide leadership award but was let go along with 23 others because of the district’s new strategy for letting new principals pick their own assistants.

“That was a bad situation,” Arnold said. “I think he was a good guy and he seemed to be doing good work.”

After Muñoz left the district — he ended up taking a principal job in Pike Township, and did not respond to a request for comment — IPS said it would embark on a variety of initiatives to increase the diversity of its staff, including hiring a district recruiter.

IPS is not alone in struggling to recruit a diverse teaching staff. Bilingual teachers are in demand across Marion County and beyond, Arnold said, because school districts have recognized that students thrive when they have mentors who share their experiences.

Arnold said IPS has a hard time recruiting those candidates because of its low pay.

“They can pretty much write their ticket to any district,” she said.

The benefits increasing staff diversity in IPS are clear to Rangel.

A shy Latino boy in his class suddenly spoke up one day after Rangel had his class read

“Esperanza Rising,” a novel about a girl struggling to adapt to life in America after she moves from Mexico during the Great Depression.

“He … starts telling us his story about coming to America,” Rangel said, “Hiding from scary men and how his mom had to leave him behind with his grandparents in Mexico, and then he came later. He still has an older brother there.”

This was, Rangel realized, a breakthrough moment.

“He said ‘I knew you’re Mexican, so you’d be OK with me sharing,’” Rangel said. “I think (my students) are less afraid to take risks, and as an adult I realize that those are the things that make or break you.”

Hayleigh Colombo is the reporter for Chalkbeat Indiana, a nonprofit news website that reports on educational change in Indiana. Email her at hcolombo@chalkbeat.org.

About the series

This is part of a series on English language learners through a collaboration of WFYI Public Media, Chalkbeat Indiana and The Indianapolis Star.

DONATE

DONATE

View More Articles

View More Articles

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.