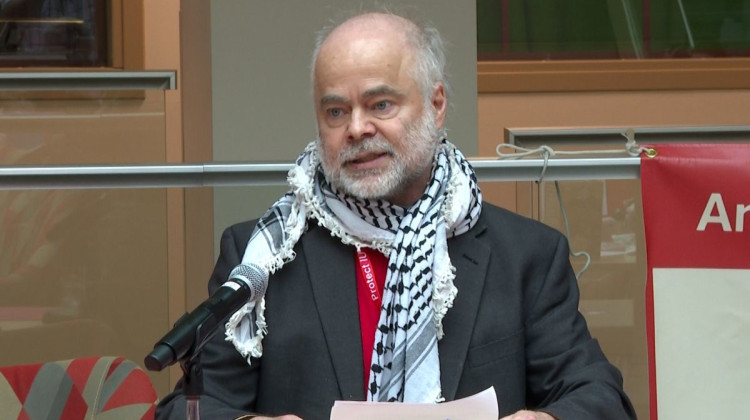

Barbara Brouwer, principal at Southport High School, poses for a photo with Elly Mawi, the recipient of a Lilly Endowment Community Scholarship on Wednesday, April 15, 2015. Photo by Kelly Wilkinson/The Indianapolis Star.

Elly Mawi found support and acceptance in Perry Township that she'd never encountered before

It never occurred to Elly Mawi that there were places where a plastic card guaranteed unlimited access to books.

For the two years she spent in a Malaysian refugee camp, school meant a dirt floor without desks or chairs. She fled there from Burma, a country wracked with civil war, after her father and grandmother were killed in a car accident. They had gone for medical care, which wasn’t available in their village.

Not until she arrived in New Bern, N.C., did Mawi discover libraries. A caseworker took Mawi and her sister, Htayni Sui, to get library cards.

“She told me I can borrow all the books I see for free,” Mawi said. “I could not believe it.”

At Southport High School, where 19-year-old Mawi will graduate third in her class, efforts to educate immigrant students have gone far beyond the academic skills they’ll need to graduate.

The school has also changed much about the way it operates to give children learning to speak English the tools they need to navigate their new worlds.

Books, in particular, made the difference for Mawi in learning English.

“If I were to measure me from my past to my present, and hopefully to the future, it’s amazing how far I have come,” she said. “All this is only possible firstly because of God, and then my mom and sister, but then because of my school.”

As difficult as Mawi’s journey sounds, many of her Southport classmates have traveled roads not so different.

Since 2001, more than 2,000 refugees have enrolled in Perry Township schools. Most arrive with little knowledge of English, and many emigrate from Burma.

This year, almost 22 percent of Southport’s students are still learning English. Most are Chin, a Burmese ethnic minority, who are increasingly drawn by the school district’s reputation for serving them well.

That’s a point of pride for Principal Barbara Brouwer, but it’s been a difficult road that has irrevocably changed Southport.

“Once they enter, their clock starts as far as they have four years to graduate from high school,” Brouwer said.

A Wake Up Call

The blaring fire alarm on an otherwise regular school day at Southport was not a scheduled drill.

Students and teachers poured out onto the building’s grounds. But there wasn’t a fire. No, they had a prankster, Brouwer figured.

On the security tape was a girl casually walking through the hallway, dragging her fingertips absentmindedly along the textured cinderblock wall. When they landed on a fire alarm jutting out of the wall, her fingers gripped and pulled it.

She kept walking. For a few seconds, nothing happened. Then sirens started shrieking.

Brouwer sent two police officers and the assistant principal to pull the girl from gym class. The girl was confused, but knew she was in trouble. Only when she burst into tears did Brouwer realize what had happened.

The girl was Chin. She had no idea what a fire alarm was.

“We went, ‘Oh my goodness, we didn’t teach them,’” Brouwer said.

A school’s job goes beyond teaching children academic subjects. They also have to graduate ready to maneuver through the world they will live in. With the Burmese children, Brouwer realized, Southport was failing on that front.

“There’s still things that we learn every single day,” Brouwer said. “We’ve got to communicate and teach them what the rules are for school. This is OK, this is not OK.”

Since then, Southport has overhauled everything from orientation to the school to class schedules to better serve English language learners.

For example, immigrant students now often start in classes that are easier to manage without a strong grasp of English, such as gym, art and keyboarding. Classes that require lots of textbook reading, like biology or history, can come later.

Southport also developed “sheltered” English classes. They still incorporate all of Indiana’s English standards, but use different readings that are easier for English language learners to understand.

It took time to find the best strategies.

“We made some mistakes, and we learned from those mistakes and have adapted,” Brouwer said. “But that’s the really good thing about it. When you have a lot of people providing input, you can see where you made mistakes. … We grew as much as they did.”

Coming to America

When Mawi was about 13, her mother had enough of the turmoil. It was time to leave Burma.

Her mother held the family together working long hours, but it had taken a toll. Plus, the political situation in the Chin section of the country was not getting better.

“There are no human rights in my country, and especially a lot of people get persecuted for religious reasons,” she said.

In 2008, a United Nations refugee agency helped the family escape to Malaysia.

Mawi discovered she loved to read while living in the refugee camp. Occasionally, she had an English lesson. It was Mawi’s first exposure to the language, and she tried to read as much as she could to prepare for her family’s upcoming trip to the United States.

In 2010, they made it.

But school in North Carolina was difficult. Mawi didn’t know English well enough to understand how to advocate for herself. A counselor advised her against a harder math class because language learners had struggled with it in the past.

Things got better when they moved to Indiana.

Mawi’s English had improved, and she tested well enough to be in regular classes rather than those for English language learners. Finally, that meant she could enroll in the honors and Advanced Placement classes she was clamoring for.

“You don’t know sometimes without letting them try first how good they are,” Mawi said of kids like her who were new to English. “So they said, ‘You can give it a try first, and after a month you can drop it.’ So I was given those kinds of chances.”

Elly Mawi, recipient of a Lilly Endowment Community Scholarship, gets a hand on a Chemistry assignment from teacher Mark Duncan, at Southport High School, Indianapolis, Wednesday, April 15, 2015. Photo by Kelly Wilkinson/The Indianapolis Star

A Bright Future

“Gifted Hands,” by Benjamin Carson, was the first nonfiction book Mawi finished on her own. It’s still her favorite.

It’s the story of Carson’s life, from growing up from poor in Detroit to becoming the director of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital at age 33.

Mawi had to use English, Chin and Burmese dictionaries to make it to the end.

“I had to do a lot of flipping after I read a page,” she said. “I had to flip my dictionary 10 times. It took me forever to finish a book.”

In Carson’s story, Mawi saw the poverty and pain of her own childhood and a dream that matched her own: finding a way to use learning to help herself and others.

Mawi is trying to decide between pursuing math or medicine in college. Math would be easier, but medicine might be the way she could help people most.

If only her country had more doctors, she’s thought, her father and grandmother might not have had to risk the long trip to another city that cost them their lives.

“I feel like education is the most powerful weapon that I have that I can use to make change in my community for my people and for others,” Mawi said.

Life in Perry Township schools has been much better than her life in Burma, Malaysia and North Carolina, she said. Now, she has school friends, church friends and a strong community connection.

Mawi recently was talking with a friend, who is also Chin but now goes to college at Butler, when their conversation turned toward the future. The friend said she wanted to live in Perry Township as an adult so her kids could go to Southport High School, too.

Mawi agreed. She’s convinced something special is going on at her high school compared to the experiences of friends elsewhere.

“It’s not quite the same,” Mawi said. “We feel special here.”

Shaina Cavazos is a reporter for Chalkbeat Indiana, a nonprofit news website that reports on educational change in Indiana. Email her at scavazos@chalkbeat.org.

About the series

This is part of a series on English language learners through a collaboration of The Star, Chalkbeat Indiana and WFYI Public Media.

DONATE

DONATE

View More Articles

View More Articles

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.