Imani Sankofa has been waiting for housing for over a year. Critics of Indianapolis’ approach to ending homelessness want to see more investment in housing.

Ben Thorp / WFYIIn 2021, then-20-year-old Heaven Stevens was homeless on the streets of Indianapolis.

She visited Outreach, a program for homeless young adults between 18 and 24, which gives them a place to stay, lets them eat a meal and do laundry during the day.

“After I heard that, I just made a beeline for Outreach,” she said. “I was like you can eat, you can shower for free? Okay, cool.”

Outreach also got Stevens into a pool of people across the city waiting for housing. That pool is managed by a group of community partners who identify who in the city most needs to be housed –– prioritizing the elderly, those who are pregnant or fleeing abuse.

“I was like, ‘Okay I’m on a list for housing, what does that mean?’ I didn’t think it was actually real until it started happening,” she said.

After a year and a half wait, Heaven was able to get housed.

But many of the people who end up on the city’s waiting list won’t.

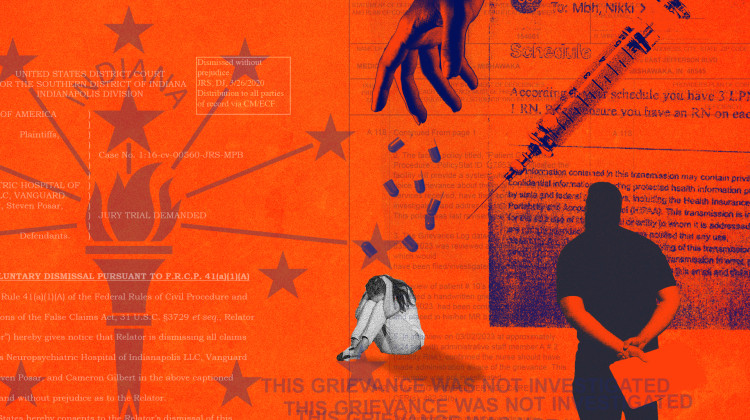

Indianapolis’ efforts to combat homelessness have been plagued by years-long waitlists and mismanagement, which has kept permanent housing out of reach for many of the city’s most vulnerable.

The city is poised to launch a new shelter –– dubbed the “Housing Hub” –– aimed at bringing 150 new beds to the homeless population. However, some community advocates say the city should instead invest more into permanent housing –– and wonder why Indianapolis can’t model efforts in similar cities where chronic homelessness has been reduced by over 90%.

Some advocates feel housing should be the priority

The total number of homeless people in Indianapolis has increased from 1,507 in 2019 to 1,701 in 2024. Of those, around 339 were classified in 2024 as “unsheltered homeless” –– people who are on the street with nowhere else to go.

The Indianapolis Housing Agency says it gives out 75 to 100 vouchers every month, but it makes only 30 vouchers available for community partners to dole out for the homeless population.

And the pool of unhoused people waiting for a voucher is regularly around 1500.

Those housing vouchers come from the federal government and are used for a variety of programs. But according to federal officials, Indianapolis isn’t making full use of the vouchers allotted to it.

One of those people on the city’s waitlist is Imani Sankofa, who said she has been effectively homeless since 2021. She has been in the city’s waiting pool for housing for around two years. For now, she stays in her car.

She said she doesn’t use the city’s shelters because she does not feel safe. She is a sexual abuse survivor and struggles with severe anxiety.

“I cannot sleep, my anxiety would be way too high,” she said.

Sankofa serves on the city’s Blueprint Council, which oversees the policies for the community organizations that run homelessness services in the city. She said she is on the council as someone not just with lived homeless experience - but as someone who is actively living it.

“So, shaping those policies, having those discussions, hearing what is being said around the table, sometimes is very difficult,” she said.

Sankofa has struggled with the city's intake system –– and said she feels stuck because she’s not part of the groups that get prioritized for housing.

“Having finally gotten on the list, or in the Coordinated Entry System, I've found that I've waited an extended period of time,” she said.

Community housing leaders don’t discount the importance of shelter beds, acknowledging they can be life-saving. But some argue shelters are akin to a bandaid and can only do so much. They say more investment needs to be put towards permanent housing options to get people like Sankofa into a safe place.

“Shelter that has low to no barriers for people to come in and be safe and warm is vital. Shelter does not solve homelessness though,” said Chelsea Haring-Cozzi, executive director of the Coalition for Homelessness Intervention and Prevention, or CHIP.

Haring-Cozzi said she is worried about the city’s plan to invest in a new shelter instead of devoting more resources towards actual permanent housing.

“I think that's where we come to this crossroads of if we are really looking for solutions, and wanting to end homelessness here in Indianapolis, we have to make sure that we are scaling and investing in housing first, and housing solutions,” she said.

Haring-Cozzi is not alone in worrying about the city’s investments in a new shelter.

Rabbi Aaron Spiegel, the executive director of the Greater Indianapolis Multifaith Alliance and a housing advocate, said the ‘Housing Hub’ as a point of contact for services is a good idea –– but it isn’t a real solution.

“We know we could end chronic homelessness in Indianapolis in a short period of time,” he said. “We know what works, the data is irrefutable. And yet, we don't do it.”

Other cities see success in prioritizing housing

Indianapolis’ officials say the low-barrier shelter will help meet the needs of the homeless by providing wraparound services while also getting them into the pool for more permanent housing.

But critics regularly point to other cities that have made strides in reducing homeless populations.

One of those cities is Milwaukee, which in 2022 was recognized by the federal government for having the lowest per capita number of unsheltered homeless in the country.

Officials there, including Milwaukee County Housing Administrator Jim Mathy, say it’s because of an aggressive prioritization of housing. He said their success is due to a “laser focus” on permanent housing, “not shelter, not transitional” housing.

Milwaukee, like many places across the country, faces a shortage in affordable housing units. Mathy said the county hired a landlord engagement coordinator whose sole job is to find units across the city and develop relationships with landlords.

“So in a rental market, as tight as ours, her sole job is finding units,” he said. “And we were surprised how many units we could find with a dedicated staff person just doing that work, because we're competing for units, just like everybody else in the community is right now.”

Once a unit is identified, the county works with individuals who are homeless to get them matched.

“We're going to pay the security deposit, and the tenants are going to pay 30% of their income, we're going to pay the rest,” he said. “But we found even with our investments and services, we are saving a ton of taxpayer money, everything from criminal justice costs to health care costs.”

In one case, Mathy says prior to being placed into housing, an individual utilized emergency room services 105 times in 90. In their first 90 days in housing, that person used emergency services just once.

While research directly tying housing to improved health outcomes is limited and inconclusive, housing has long been considered a social determinant of health and accepted as one factor contributing to good health.

The county also points to internal data showing that 98% of the homeless individuals who enter the program receive a citation in the 12 months prior to being housed. In the first 12 months after being housed, that number drops to 9%.

“It's the perfect metric of improving the quality of life for individuals who are really vulnerable, but it's also a really good financial investment,” Mathy said.

He said the initiative is possible because it has largely been managed by the county under one roof –– from vouchers to placement to outreach on the street.

In Indianapolis, homelessness services are managed by some thirty partners.

Indianapolis also faces a major hurdle with its voucher program. Earlier this year the federal government stepped in to take over the Indianapolis agency that oversees housing vouchers.

“The voucher program wasn’t working right. Not much was working right,” said Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary Richard Monocchio at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, during a press conference in April.

According to Monocchio, roughly 17% of the city’s housing vouchers were not being used because city officials “did not want to put in the hard work.”

Over three months later, officials with the city still say making more vouchers available is not the priority.

“The answer is yes, they [the IHA] would always like to have more vouchers going out, however, the top priority right now is to serve residents who are already in IHA’s system,” said Aryn Schounce, senior policy advisor to the Mayor tasked with overseeing the recovery of the Indianapolis Housing Agency.

HUD’s oversight of the IHA was also initiated because of concerns about the living conditions of residents already within the city’s system. Schounce said those residents are a priority.

“It’s a difficult pill for folks to swallow because of how long IHA has been crumbling as a housing agency but there is a lot of very good work going on at IHA right now,” she said. “But this will take time.”

Andrew Merkley, director of Homelessness and Eviction Prevention at Indianapolis Mayor’s Office of Public Health and Safety, acknowledged that the city is not moving people into housing fast enough.

“The community's plan to end homelessness wants to reduce that time that it takes to get housed,” he said. “And I think right now, we're not meeting the goals in that plan.”

Other city officials underlined that changes to Indianapolis’ housing landscape won’t take place overnight, but also said the city is investing in housing solutions. Those officials point towards affordable housing projects across the city that sometimes include units for those experiencing homelessness.

But with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling earlier this summer allowing cities to remove homeless residents sleeping outdoors, community leaders say efforts to improve the city's homelessness programs can’t come fast enough.

Side Effects Public Media is a health reporting collaboration based at WFYI in Indianapolis. We partner with NPR stations across the Midwest and surrounding areas — including KBIA and KCUR in Missouri, Iowa Public Radio, Ideastream in Ohio and WFPL in Kentucky.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.