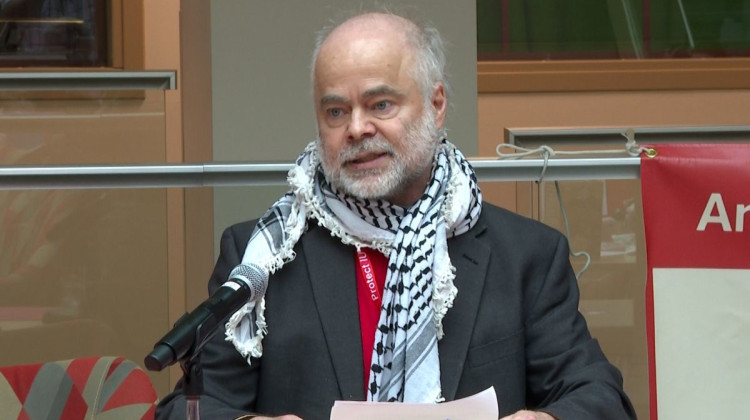

Jessica Ramirez, pictured in her classroom at Northside Middle School in Elkhart, Indiana, in December 2021, works with a student during lunch hour. Ramirez is a veteran special educator. She said the struggle to hire special education paraprofessionals makes it harder for educators to do their jobs.

Dylan Peers McCoy/WFYIWhen Mary Tackitt first took a job as a teaching assistant for students in special education, it seemed like a good opportunity. She enjoyed the time with children — like the little boy who would hold her hand and tap it on the desk to keep rhythm with music. But working with students with severe disabilities was tough. She took them to the bathroom and changed diapers. And she was hurt on occasion by those who struggled to regulate their emotions.

Tackitt, who worked for Indianapolis Public Schools, made just over $15 an hour.

“The more I had to be bit by kids and the more I had to take them to the bathroom and get fecal matter on myself, the more I just kind of realized that it wasn't enough,” Tackitt said.

She resigned this spring, after less than a year in the job.

Teaching aides, or paraprofessionals, play a crucial role in educating students with disabilities. As staff who are not licensed by the state, they are often overlooked in debates and policy fixes around teacher shortages. These aides are the backbone of many classrooms, as they help students with their behavior and school work, and care for children with significant medical needs.

But at a moment when state tests show that students with disabilities need help to recover from the academics they missed during the pandemic, school administrators across Indiana struggle to keep and hire special education assistants.

It’s a nationwide problem that some school leaders say has gotten worse during the pandemic and due to the surging labor market.

“I think we're at an all time high,” said Laurie VanderPloeg, a former director of the Office of Special Education Programs in the U.S. Department of Education. “This is definitely a crisis.”

Federal data on paraprofessional staffing levels is a couple years out of date, so it’s hard to confirm whether the pandemic worsened the chronic problem, VanderPloeg said. Many assistants, however, left the field because their hours were cut or they were furloughed when schools were closed or remote. Then, the competition for workers increased.

“So we are competing with a McDonald's or you know, even some of the local stores that are paying up to $13 or $15 an hour,” she said.

VanderPloeg is now associate executive director for professional affairs of the Council for Exceptional Children, an advocacy organization for education professionals that offers memberships and online training for special education assistants.

A chronic problem with limited data

There is no source of reliable statewide data on the number of special education assistant positions that are vacant in Indiana. But it is likely hundreds. Fort Wayne Community Schools has about 110 vacancies for special education teaching assistants. In the state's southwestern corner, Evansville Vanderburgh School Corporation had nearly 20 openings posted online in mid-August. In Marion County, Perry Township Schools has about 30 jobs available, and Indianapolis Public Schools has about 40.

The shortage of special education teaching assistants is persistent in IPS, according to district officials. The school system, which currently has about 170 special education paraprofessionals on staff, had slightly more vacancies last year. The district said it has increased pay for teaching assistants in recent years, and pays higher wages to those who work with students with severe needs, like Tackitt did.

When schools don’t have enough teaching aides, it’s a problem for the whole system. Many school districts are struggling to hire qualified teachers for students with disabilities. Indiana, like almost all states, is facing a shortage of certified special educators. With fewer teachers and teaching assistants, there’s more work for the existing staff members to manage.

“When we face a staffing shortage, we work really hard to do the best we can with the people that we have. And, you know, does that impact what we can do for kids? Likely, yes,” said Angie Balsley, president of the Indiana Council of Administrators of Special Education.

That can lead to legal action against schools because students with disabilities are entitled to special education services. And it makes the job harder for existing special education staff members.

“We are burning out our professionals,” Balsley said. “That's going to just perpetuate the problem, because folks will leave due to the level of stress and workload.”

Challenge for schools and teachers

Jessica Ramirez is a veteran special education teacher at Elkhart Community Schools in northern Indiana. The district has 14 open special education paraprofessional positions.

Ramirez said those missing assistants “greatly affected” the district’s ability to provide services and instruction to students.

“We've already been working on how to do things differently as teachers, because we have lost our [paraprofessionals],” Ramirez said. “Even if there is somebody that could be hired, there's no person who wants to do that, for the limited wages that they do receive.”

Bluffton High School Principal Steve Baker had to hire three special education teaching assistants this summer. That’s nearly half the total number of assistant positions at the rural high school south of Fort Wayne.

To make the job more attractive, the Bluffton-Harrison district substantially raised pay for teaching aides this year to about $15 per hour. Still, Baker had zero applicants in the weeks before the start of school on Aug. 10.

So he did some personal recruiting. “I started calling my best subs,” he said. Then, Baker approached bus drivers to work as teaching assistants between their morning and afternoon routes.

Baker filled the special education assistant vacancies — including with one bus driver who is also working as an aide.

Jeanine Corson, chief human resource officer for New Albany Floyd County Schools, said she tries to woo candidates by telling them about the regular, weekday hours they would work and holidays off.

The 12,000-student district boosted minimum pay to about $14 per hour and increased recruiting. That helped, Corson said. But the school system listed nearly 30 job openings on its website in mid-August.

"Everybody is fighting for the same candidate pool, and you have to compete with Target, who can raise the prices of what they sell to raise the wages for their employees,” Corson said. “We don't get to do that.”

Paraprofessionals in Indiana made an average of $27,000 a year in 2021, according to federal data. Many districts have raised pay over the past couple of years. But wages still remain low.

VanderPloeg of the Council for Exceptional Children said schools received a huge influx of cash from the federal government to support students during the pandemic. School administrators have raised concerns about spending that money on increased salaries, because the funding runs out after a few years.

But VanderPloeg said schools facing shortages should spend some of that money on wage and benefit increases for their special education assistants. Otherwise, students could miss out on necessary services and schools may face legal action, VanderPloeg said.

VanderPloeg believes that if schools invest the money well and improve education for students, federal lawmakers will have an incentive to sustain funding.

“I hear many of the states say, ‘we don't want to use our money on personnel.’ But that's your greatest deficit, is personnel,” she said. “So spend the money. Start developing a system. And then continue to ask for funding for sustainability.”

Why teaching assistants quit

While districts say they cannot afford to raise wages for teaching aides, the low pay and benefits mean many assistants can’t afford to stay on the job.

Sari Lawton was a special education teaching assistant at Hamilton Southeastern Schools — an affluent district in suburban Indianapolis. After close to seven years on the job, she made about $18 per hour.

That’s more than many special education assistants. But because of unpaid summer and school breaks, she had to work side jobs as a nanny and tutor.

Lawton’s biggest problem was health insurance. She was not on the district’s plan because the premiums were too expensive.

Hamilton Southeastern would have charged Lawton almost $425 per pay period for the health plan she thought was best for her and her daughter. That adds up to about $7,190 per year. Teachers in the district pay less than half that cost for the same coverage because of the benefits negotiated in their union contract.

Lawton resigned this spring.

She now works for a financial planning firm where she makes more money and gets affordable health insurance.

“I felt sad leaving. I really didn't want to leave, but I didn't have much of a choice in the matter,” Lawton said. “There's got to be some sort of way to make it better where you can actually make enough money to survive.”

Contact WFYI education reporter Dylan Peers McCoy at dmccoy@wfyi.org. Follow on Twitter: @dylanpmccoy.

Contact WFYI education reporter Lee V. Gaines at lgaines@wfyi.org. Follow on Twitter: @LeeVGaines.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.