Jessika Osborne, ESL coordinator and Title 3 Coordinator for Manual High School, left, talks with Lester at Emmerich Manual High School, Monday, July 31, 2018. Lester moved to Indianapolis when he was 15 years old and is set to graduate from Manual in 2019. Lester, an undocumented immigrant from Honduras, dreams of going to college. He hopes that football will help him pay for that dream. (Photo: Kelly Wilkinson/IndyStar)

This story was produced by the Teacher Project, an education reporting fellowship at Columbia Journalism School, as part of an ongoing series on the intersection between education and immigration.

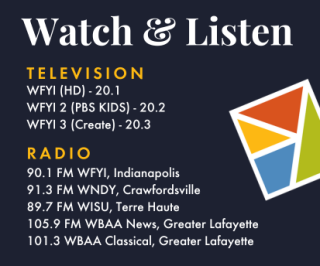

In collaboration with WFYI, the Teacher Project will host a panel discussion on college access for undocumented students on Aug. 15. The event will be from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. on Aug. 15 in the Reuben Community Room at WFYI, 1630 N. Meridian. For more information, including RSVPs, click here.

BY MIKE ELSEN-ROONEY, THE TEACHER PROJECT

On a campus tour of Ball State University last fall, 17-year-old Lester Gomez gawked at the 20,000-seat football stadium, the red-trimmed locker rooms and the gleaming engineering computer lab. It was the Honduran immigrant’s first trip to a university in the U.S.

Eagerly, he quizzed the tour guide about the central Indiana university’s minimum GPA, graduation rates and tuition costs.

Lester, who just started his senior year at Manual High School, is on track to graduate with an Indiana Honors Diploma for students who complete college-level work in high school.

His teachers speak glowingly of his work and potential. His football coach said Lester, a talented recent convert to the sport who can kick a 40-yard field goal, has a shot at an athletic scholarship.

Yet the path to college remains arduous — and unlikely. Lester, whose immigration status is uncertain, arrived in the U.S. two and a half years ago after a long journey stuffed inside a tractor-trailer with 50 other migrants.

Officials have allowed him to remain in the U.S. until a court hearing can be scheduled to determine his long-term fate. So, at least for now, Lester is living here legally. That said, his status doesn’t allow him to qualify for state or federal financial aid because he doesn’t have a green card.

That means his parents, who make a combined $35,000 annually as a used furniture saleswoman and Buffalo Wild Wings cook, would likely be paying full freight.

Moreover, most high schools, including Manual, lack expertise — or even basic awareness — of how to guide students in Lester’s situation through the college application process. “High schools are doing very little,” said Monica Medina, an associate professor of education at Indiana University.

Medina said guidance counselors rarely “feel confident about what to do.” That can leave students like Lester largely on their own when it comes to complicated tasks such as figuring out how to take college entrance exams without a federal or state ID or locating private scholarships for immigrant students.

Approximately 1 million students whose legal status is unclear are enrolled in U.S. schools, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Every year, about 65,000 of them graduate American high schools, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Department of Education. Of those, an estimated 5 to 10 percent enroll in college; an even smaller percent graduates.

To be sure, how best to handle children who have entered the country illegally is a contentious issue. Some argue that children who have done well in school should be afforded the opportunity to be full contributors in the U.S., regardless of immigration status. Others feel just as strongly that students who are not U.S. citizens should not receive assistance such as financial aid or in-state tuition — benefits that should be reserved exclusively to students who are in the country legally.

But for Lester the issue is more simple. He is here. And he wants to make the most of it.

Pursuit of the best education possible has shaped many of his actions over the last 17 years, and he isn’t ready to abandon the quest now. With the threat of deportation always looming, the teen plans to apply to several colleges, including Ball State, this fall.

His story speaks to the financial, legal, and practical obstacles that put college out of reach for tens of thousands of students whose immigration status is unresolved. But it also speaks to an undying faith that, in America, anything is possible.

“There are a lot of opportunities, and if you don’t take them, it’s like you are sleeping,” Lester said.

“I really want to go to college. It’s like a dream.”

The Winding Path to Indianapolis

Fifteen and a half years ago, a 19-year-old seamstress with a sixth-grade education set off alone from El Progreso, Honduras, without telling her parents. The woman, named Johana, left behind her 2-year-old son, Lester, not knowing what dangers the journey to the United States had in store.

Lester’s father had disappeared before his son was born, but Johana felt confident that the toddler would be safe staying with his grandparents. The decision to leave, Johanna said, was excruciating. She hoped that in the U.S. she could find a job and send home enough money for Lester to attend a private school, since the city’s public schools were notoriously violent.

Johana eventually settled in Indianapolis, where an aunt lived, and began selling used furniture out of her garage. When Lester turned five, she started sending $300 a month to pay for his tuition at a private, Catholic school in Honduras.

Johana married a Guatemalan man with a green card, and they had three children of their own, all U.S. citizens. But she talked to Lester on Skype every day of his childhood.

“It’s very ugly,” she said in Spanish, “to have a piece of yourself in another place.”

In El Progreso, Lester attended school daily, went to chapel at school every Monday and Friday, and played pickup soccer with his friends many afternoons. He excelled in computer science and math, joining an after-school program to fix old computers three days a week. There, he started thinking about how college would allow him to “get deep into computer science.”

One fall afternoon three years ago, two older teenagers approached Lester as he walked home from school. Their arms were covered with tattoos, and they wore decorative bandannas over their faces; one wore black, the other green. They told Lester, then 14, that they knew all about him: when he got out of school, which bus he took, where his grandparents lived.

The teens were members of the notorious MS-13 gang, and Lester realized that he had been targeted for recruitment. “I was like, ‘What did I do?’”

Gang members even threatened Lester’s 54-year-old grandmother as she walked home one day, telling her they would kill her if Lester didn’t join them. The family’s fear deepened when his mother missed some private school tuition payments, so Lester briefly had to transfer to a public school — one where some of his classmates were members of MS-13.

During Lester’s adolescence, the murder rate soared in Honduras, reaching 130 per 100,000 residents in Lester’s city of El Progreso in 2012, according to a report from the World Bank. MS-13 was responsible for much of the violence as the gang expanded its territory and battled with rival groups.

After the threats, Lester and his grandmother knew the family was no longer safe. He had to leave Honduras. “It wasn’t a choice,” Lester said. He had just two days to pack his belongings and say his farewells. “I could only put him in God’s hands,” his grandmother said, speaking in Spanish, during a phone interview.

On Feb. 21, 2016, Lester checked into a hotel near his grandparents’ home; a car picked him up at 3 a.m. the next day and set off for the Guatemalan border.

A Legal Scramble

Hundreds of thousands of immigrant children are, like Lester, stuck in a legal limbo.

According to the Transactional Records Clearinghouse, a data organization based at Syracuse University, about half of the more than 200,000 young immigrants who’ve arrived at the U.S. border since 2004, most of them fleeing gang violence and civil unrest in Central America, are in the same position as Lester: They can stay until a court date, when a judge will decide whether to expel them.

Those court dates are typically long in coming: The average wait for an immigration hearing in Chicago court is over 1,000 days.

In a two-year span from 2014-2016, asylum officers approved only 37 percent of the almost 6,000 unaccompanied minor asylum claims they reviewed across the country, according to an Associated Press investigation. The regional office in Chicago that would hear Lester’s case had OK’d only 15 percent of applications — the lowest rate in the country, the investigation found.

Earlier this year, Attorney General Jeff Sessions ruled that fear of gang violence does not qualify a migrant for asylum.

Under federal law, all students must be allowed to attend public K-12 schools, regardless of immigration status. Shortly after Lester arrived in 2016, his mother easily enrolled him at Manual High without delving into her citizenship status. She chose the school because the bus route passed their home and she had heard it offered English classes for new immigrants.

But unlike K-12, college access in Indiana is inextricably tied to immigration status. Students such as Lester do not qualify for federal financial aid like the Pell Grants that help millions of low-income students attend college; and they can’t receive federally subsidized loans, which require the co-signature of a U.S. citizen.

And in at least six states, including Indiana, they also can’t access the heavily discounted in-state tuition rates at public universities. (Young immigrants known as “Dreamers,” who, unlike Lester, arrived in the country before 2007, are protected by President Barack Obama’s 2012 DACA order and can sometimes qualify for in-state tuition rates in Indiana.)

Without an athletic scholarship, Lester would be paying $24,000 in tuition each year at Ball State — two-thirds of his parents’ income. Most Indiana residents pay $8,000.

In 2011, the Indiana state legislature passed a law restricting in-state tuition rates to students “lawfully present” in the country.

Republican State Sen. Mike Karickhoff of Kokomo, who authored the bill, said the rationale is simple: Students who “have not contributed … to the tax base that helps operate these colleges” should not get the benefit of the discounted rate.

In January, State Representative Earl Harris Jr. of East Chicago introduced a bill that would allow anyone who has lived in the state for three years and graduated high school to qualify for in-state tuition. “We have a shortage of skilled, trained people in Indiana,” he said, adding that many state universities are under-enrolled.

Lester’s family is desperate to find a way for him to stay for the long term. Before the teen decided to flee Honduras, Johana had for years been on a crusade to bring her son to Indianapolis legally.

Twice, Johana and her husband have been the victims of real-estate fraud, targeted by criminals who prey mostly on Latino immigrants. The first time, in 2012, the couple bought a $23,000 ranch-style house in East Indianapolis from a woman who gave them a fake deed.

The city actually owned the property. The man in charge of the city agency that resold abandoned properties, Reginald Walton, agreed to sell the house back to the family for a discounted rate.

But shortly after that second transaction went through, in early 2013, Johana received a call from the FBI. They told her Walton — who was later convicted of accepted bribes and kickbacks in the land bank fraud scheme — had defrauded her again, overcharging the family by several thousand dollars. She was wary of cooperating with the FBI, concerned that Walton might seek revenge. But they made an offer that changed her calculus, she said.

The agents promised to help her apply for an ‘S’ Visa — known colloquially as the “Snitch Visa.” It is a little-known law enforcement tool that officers can offer as an enticement to testify in criminal investigations.

Only 200 such visas are handed out each year, according to the U.S. Department of Justice, and the agents didn’t make any guarantees. But they submitted an application on Johana’s behalf and set her up with a pro-bono lawyer.

An S Visa would mean a path to permanent residence for Johana, and, most temptingly, a legal way to bring Lester from Honduras. “In my mind, Lester was going to come,” she said.

Johana testified and helped secure the conviction of Walton, and his accomplice David Johnson. The trial took about a year, and while the S Visa application was pending, she obtained a temporary work permit and social security number. She bought a vacant property across from their house and opened her own used furniture business. Things were looking up.

But a couple of months after her testimony wrapped up in late 2015, Johana learned that Lester was bound for the U.S. on his own, a decision that both angered and scared her. It also complicated her plan to bring him to Indianapolis legally.

Then, in the fall of 2016, Johana learned that officials at Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) had decided her case did not merit an S Visa. The decision came without explanation, but it was not unusual: Immigration advocates have criticized the FBI for dangling S Visas as an incentive for witnesses to cooperate without actually following through. A spokesperson for the FBI declined to comment, referring questions to the Department of Homeland Security.

A Legal Aid Society lawyer representing Johana pro bono agreed to help her apply for a green card through her husband, Edgar (already a permanent resident), but the lawyer said she couldn’t take on Lester’s case.

Johana decided the family’s limited resources would better be spent on legal fees for her husband’s citizenship application. Edgar passed the citizenship test in July. The family now plans to apply for a green card for Lester as the stepson of a citizen.

But they haven’t been able to afford a lawyer for Lester, and have missed key deadlines as a result. Since Lester turned 18 in early August, it will be harder for him to obtain a green card through his parents. He could be called to court any day.

An Uncertain Educational Future

From his first day at Manual, Lester was determined to excel.

“He put himself out there,” said Manual’s English-as-a-second-language (ESL) instructor, Jessika Osborne. “He didn’t let the language barrier keep him from doing that.”

Lester’s athletic abilities — he’s now a part of the school’s soccer, football and wrestling teams — have helped him acclimate socially. So has his playful sense of humor: He has a personal nickname for most of his classmates and even some of his teachers — Jessika is “the famous Osborne.”

Lester still loves math and takes an honors-level class in the subject. He’s progressed rapidly in English, thanks in part to the time he spends around English-speaking peers. Lester’s English was strong enough for him to test out of the ESL program last spring, although he elected to take another class with Osborne this year.

Manual has become a destination for immigrant and refugee students since it was taken over by the state and, in 2011, turned over to a charter operator. Seven years ago, the ESL program enrolled three students. Now it serves more than 80.

Yet the school — like most — still has little expertise in how to help even the most successful students who are facing immigration issues navigate their way to college.

High schools seldom know how to counsel such students through the college admissions and financial aid process, said Guadalupe Pimentel Solano, a 26-year-old activist with the Indiana Undocumented Youth Alliance. Counselors lack basic knowledge about private scholarships that might be available to students such as Lester and don’t how to talk about sensitive legal issues, she said.

Solano wishes high schools would do more, such as making information so accessible that students don’t need to disclose their status to access it.

Carmen Lynch, one of Manual’s two guidance counselors, said no student in her six years at the school has confided to her that they may be in the country illegally. That makes it hard to know how to help them. “I don’t know how to overcome that challenge in getting kids to feel safe telling us, so we can find the universities that will still enroll them,” she said.

Lester met once with Lynch to talk about Ball State, but he didn’t mention his immigration status. He said he might bring it up this school year.

Those conversations take time and trust, Osborne said. Lester first told her his story after more than a year in her class. “You can’t push these relationships,” she said.

Because Osborne knows Manual’s immigrant students better than most of the other teachers, she has found herself stepping into a new role: college advisor. That includes developing relationships with colleges and searching for scholarships.

It’s not easy. Osborne recently signed up a batch of students to take the SAT — only to realize that few had the legal ID card (driver’s license, passport or social security card) required to take the exam.

“My stress is that that’s all on me,” Osborne said. “And that’s not my job.”

So far, none of Osborne’s estimated 50 students who face immigration issues have made it to college (at least among those who aren’t protected under Obama’s 2012 DACA order). Many of them, especially the Hispanic male students, drop out to work full time. Others become overwhelmed by the bureaucratic nature of the financial aid forms. Or they decide they don’t have a reliable way to attend college classes without a driver’s license. “It’s too much,” Osborne said.

This fall, Lester will take the SAT for the first time, as well as some college-level courses.

For his family, the priority has always been education. Three of his closest friends dropped out of high school last year to work full time and support their families.

But Johana is dead set against Lester following a similar path. “At four years old, I told them all, ‘Your job is to study. And we’ll do the rest,’” she said. Lester wants to help his family financially. So by way of compromise, he has a weekend job as a roofer and chips in for the family’s internet bill.

But he knows little about the practicalities of the college admissions process. And even the local community college, the cheapest option, would cost Lester $8,000 a year in tuition, compared to $4,000 for in-state residents.

His options for finding a job to defray the costs are limited: Without a change in his legal status, he can’t obtain a work permit or a driver’s license.

Lester said he felt a twinge of resentment when a classmate recently mentioned that he overslept a driving exam. “I was like, ‘wow bro,’” Lester said. “You know how hard it is for us to get a driver’s license?”

But he doesn’t let that resentment linger. “I wouldn’t judge someone,” he said. “Everybody has his opportunity someday.”

It’s still tough for Lester to open up about the hardest parts of his journey, even with his mother. “We barely talk about it,” she said.

Osborne said it would be tough for the casual observer to recognize how much hardship Lester has already endured.

“I think every day,” she said, “‘How did he have that story?’ You would’ve never guessed. He’s definitely the light of my classroom.”

Lester knows the future might bring more setbacks. It makes him even more determined to make the best use of the time he has — even if he never makes it back to Ball State for a longer stay.

“I would still be glad (that I came to the U.S.) because I finally met my family,” he said. “I studied. I didn’t waste my time.”

DONATE

DONATE

View More Programs

View More Programs

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.