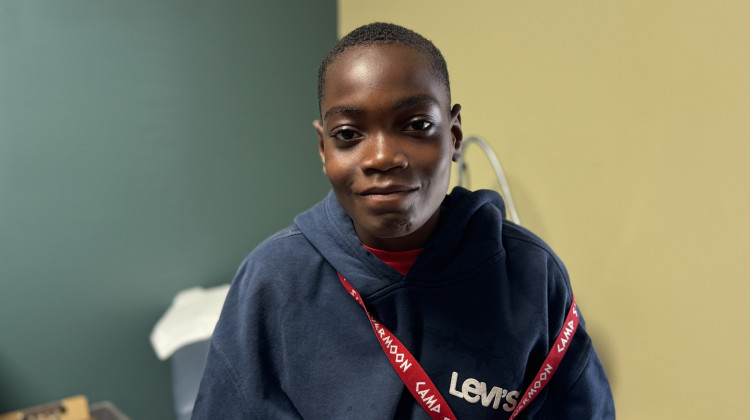

Tobi Ajayi, 14, is one of the campers. He said the camp provides him with much needed bonding and socialization time.

Elizabeth Gabriel / Side Effects Public MediaSunscreen, bug spray and a plushie. These are some of the things children prepare as they head to summer camp. But for children with sickle cell disease, that list looks a lot different.

The genetic blood disorder, which causes their blood cells to get jammed in vessels, can send them into sudden extreme pain crises, and potentially cause life threatening emergencies.

Camp staff have to make sure campers get their medications on time, avoid extreme changes in temperature, and ensure they have access to trained medical staff in case they go into a pain crisis. Summer camps are typically not prepared for it.

But Camp Silver Moon, a week-long no cost overnight camp held in North Webster, Indiana, is trying to change that.

The camp is one of less than 50 across the country for kids with the genetic blood disorder. This year, 34 kids with sickle cell disease and 15 siblings without it went tubing, played sports and participated in talent shows.

13-year-old Jordan Roddie, one of the campers, feels like everyone there gets what it means to live with such a debilitating disease –– unlike some people at his school.

“People don’t understand what it is. I had a friend who cut me off because she thought I was contagious,” Roddie, who has attended camp for 5 years, said, “which kinda hurt me.” (Sickle cell is not contagious. People are born with the disease.)

Roddie is one of the roughly 100,000 people in the country who have sickle cell disease. It’s a rare genetic blood disorder that makes blood cells change from the typical donut shape, into the shape of a banana, or a sickle. Patients suffer from a range of problems including chronic pain, strokes, organ damage and often shortened life spans. Some sickle cell patients get tired more easily, can’t run as fast or handle as much physical activity.

The disease mostly impacts Black and Latino people, but can also be found in people from the Middle East and India. In the U.S., roughly 90% of sickle cell patients are Black.

A chance to belong

The physical toll of the disease often translates into a mental one too. Sickle cell can send children in and out of hospital, making them miss school days and other activities. Some patients also experience delayed puberty, which leads to social problems and sometimes bullying by peers.

Research shows that around half of the kids with sickle cell have chronic or acute mental health problems due to low self-esteem and social isolation. That’s why camp is important to kids like 14-year-old camper Tobi Ajayi. He says sickle cell makes him feel like he doesn’t belong, especially in school.

"It draws attention to me, like unnecessary attention, just because I want to go to the nurse or ask the teacher if I could just take a break. And sometimes, for me, I just want to be like a normal kid,” Ajayi said.

Sickle cell takes a toll on caregivers too. Olayemi Ajayi, Tobi’s mother, said paying medical bills can be overwhelming.

“At times I have to decide [if] I have to take him for this appointment, or maybe I think, ‘I don't have to go for my own appointment,’” Ajayi said. “So I have to choose between me and him at times, which is not really good for me, but I want him to be fine.”

Research shows that some caregivers can also have mental and emotional health problems.

But things are different at Camp Silver Moon. The kids say they feel equal and parents don’t have to break the bank for them to attend. Families don’t need to pay to send their children to the camp and free transportation is offered to and from the campground. But that comes with a hefty price tag for camp hosts.

Lewis Hsu, a pediatric hematologist with the University of Illinois Chicago, said staffing and funding are big barriers to holding summer camps.

“If you have children from low income families, or families whose resources have already been depleted because of medical costs, then you can't really charge them. So, then if you have a camp for 80 kids, and it was going to be $500 or $1,000 per kid, that's [at least] $40,000. So you have to figure out how to raise that money,” Hsu said.

Special preparation

Camp Silver Moon, hosted by Innovative Hematology, has about 15 extra staff — including nurse practitioners, physical therapists and social workers who already see these kids as regular patients outside of camp.

Kimber Blackwell, a physician assistant with Innovative Hematology, reminds the children to drink enough water and to be prepared for different environmental factors.

“It's keeping their cabins warmer at night, making sure they've got a blanket and making sure that they dress in layers,” Blackwell said.

Dehydration and a sudden change in temperature are two potential triggers of sickle cell pain crises. It’s why many of the children may be seen wearing a sweatshirt when the weather is warm, which can make kids feel self-conscious, Blackwell said.

Over the years, Blackwell said they’ve learned to ask specific questions on their intake forms and do interviews with families before the camp to make sure they can accommodate everyone. They also bring more heating packs and a shower chair to help with a pain crisis or if someone is in too much pain to stand while bathing.

Pushing past the pain

Last year Roddie spent most of camp in the infirmary, so he was determined to stick it out this year. He hung out with friends and played a little bit of kickball on the first day of camp. Then, a sickle cell pain crisis hit.

The pain was so bad, Roddie cried during the roughly 10 steps to the golf cart that would take him to the infirmary.

Nurses swiftly gave him water, a little snack and some pain medication.

He described the pain as needles rapidly poking him over and over again. Almost feeling paralyzed. If he tries to move, it hurts even more.

Roddie knows things could have been a lot worse if it weren’t for the preparations at the camp. In fact, outside of camp, most sickle cell patients in the U.S. struggle to access proper care because there aren’t enough medical professionals who know how to treat them.

Roddie started feeling better about an hour later.

He said on a scale from 1 to 10, his pain level managed to go from an 8.5 to a 3.

“I want to feel better,” he said. “I’m not gonna do nothing because that can trigger it more. So I’m gonna relax the rest of the day and see how it goes.”

By the end of the week, nine kids had a pain crisis, and two kids had to go home — including Roddie. But he said he’ll be back. In fact, he wants to be a counselor in a few years.

“I just want to make sure the next group that comes here, I can show them a good example,” Roddie said, because he has sickle cell, he would understand how they feel and get them the help they need.

Contact WFYI’s health reporter Elizabeth Gabriel at egabriel@wfyi.org.

Side Effects Public Media is a health reporting collaboration based at WFYI in Indianapolis. We partner with NPR stations across the Midwest and surrounding areas — including KBIA and KCUR in Missouri, Iowa Public Radio, Ideastream in Ohio and WFPL in Kentucky.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.