Thousands of residents in long-term care facilities across Indiana have been infected with COVID-19.

Brock Turner/WFIU-WTIU NewsLong-term care facilities across Indiana are disproportionately affected by COVID-19. A lack of reliable data is crippling the response.

Since April, Indiana has been collecting daily COVID-19 updates from every long-term care facility in the state. Yet, after months of prying from journalists and trade organizations, state health officials insist on keeping the data from the public.

In the Midwest, Indiana is alone. Ohio, Illinois, Michigan and Kentucky all provide public, facility-level updates on COVID-19 in long-term facilities.

Many Indiana counties are analyzing data the Indiana State Department of Health is collecting to inform decisions. Some have opted to make it public, others have not.

Around a half dozen Indiana counties say they received direct guidance from ISDH not to release facility-level data to the public.

That's something the state denies.

“To my knowledge, no one from the Indiana State Department of Health has ever directed anybody that they should not release their data,” State Health Commissioner Dr. Kristina Box said during a press briefing last week. “We have supported them releasing their data if they desire to release their data.”

Privately, the department opts for a different tone. Earlier this month, the department’s Deputy Health Commissioner and State Epidemiologist Pam Pontones provided talking points during a webinar for local health departments not releasing data.

“If you are asked why you aren’t receiving facility-specific information you can reference you are following the communication guidelines for long-term care facilities on the link on the slide,” Pontones said.

Local health departments say they’ve received directives via email and over the phone from ISDH representatives not to release data.

COVID-19 disproportionately affects older populations and people of color. The extent is unclear, in part, due to data inaccuracies.

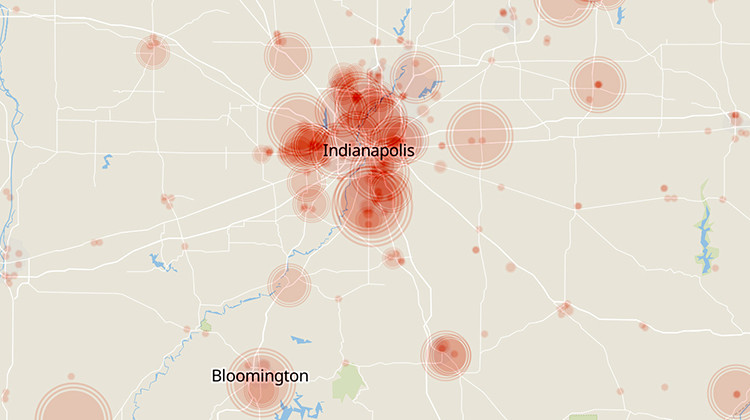

According to the most recent data ISDH released on June 15, 264 facilities in Indiana have at least one confirmed COVID-19 case. One hundred and sixty-four facilities have seen at least one coronavirus death.

All together more than 1,000 Hoosiers in long-term care facilities have died of coronavirus, and nearly 5,000 have been infected.

However, that’s all the state is releasing publicly.

In a response to complaints from other media organizations, Indiana Public Access counselor Luke Britt last month defended the department's position, writing: "From my discussions with ISDH, those goals are not mutually exclusive with the agency - they simply do not have a running tally, database or spreadsheet with that information. They address those concerns in alternative ways."

Indiana's State Department of Health isn't the only organization compiling data. The federal government also required Medicare-certified facilities to report data. However, problems and data inaccuracies have been well-documented.

State and federal numbers — both reported directly from facilities — don’t match. Nearly everyone recognizes that the data is flawed.

“The fact that we cannot get our arms around good data, it’s frustrating for us public health officials,” Angela Cox, administrator for the Henry County Health Department, says. “It is really confusing the public. It’s making them nervous. They’re starting to doubt our infrastructure, and why wouldn’t they?”

Cox says for years public health officials like herself believed there was a plan in place to deal with a global pandemic, but even she now has doubts.

For many of us, the first time in our careers [we] are struggling with the fact that we thought we had a plan. The science is there. The epidemiological models and the processes are there. We use them for other things and they are working,” she says. “We’ve talked for years about something of this magnitude and now that it’s here I think we have our eyes open to the fact that we were not ready for the magnitude of this.”

Cox doesn’t place blame on a single entity, but says precursors and warning signs were present.

She points to measles outbreaks within the past couple of years and overall public health funding in the state.

“This is proof of what’s happened. Indiana [is] 47th in the nation as far funding of public health. This is what you get."

Other reports place Indiana even lower.

“When I did a review of the books in the five years prior to me taking the position the local public health department in Henry County had lost around $120,000 in tax levy funding because of cuts," Cox says.

She says lives have been lost in Indiana and her county because of declining public health funding.

Data Without Context Causes Concern

For Stephanie Borem transparency and public health funding is more than politics or policy — it's personal. Borem works in health care and is helping care for her father, Chris Nicolini, with Alzheimer’s Disease.

Borem says she knew something was wrong when she noticed the man who spent more than 40 years of his life coaching football and track becoming overwhelmed attending athletic events last year. She recalls the last time her dad stayed with her and her family while her mom was traveling.

“He stayed with us while [Mom] went on her big retirement trip and then by the time she got back he had declined so much it pretty much became a 24/7 job.”

Borem says she’s thankful the Hobart facility her dad lives in has been transparent. They provide regular updates along with quality care, but she suspects residents in other facilities are not as fortunate.

READ MORE: How Does COVID-19 Spread To Nursing Homes During Lock Down?

“You’re [looking] through a window and you can’t do anything,” she says. “I think so many people go through that risk when they see their loved ones. What if their clothing is on backwards and dirty and they’re dirty or not shaven or just unhappy?” she asks.

Borem says candidly, “It’s just a risk.”

She believes more data should be public, but says nuance and context are important. She believes sharing more information about mitigation and prevention could quell fears. Additionally, she believes classifying the severity of an outbreak could increase transparency.

“Information needs to be released,” she says. “I just wished everyone would understand what the numbers mean. Just because a facility decides not to test so their numbers look good does not mean there’s nothing in there.”

The context is important. Facilities are required to report this data, but health experts say there is little incentive to do so.

Cox believes the current framework puts an additional burden on facilities.

“I know for our facility, they literally had to take one person — and it wasn’t a direct care staff member, but it was someone in administration — they had to take them off their daily duties because they had to put them at the forefront of dealing with all of the phone calls.”

She admits she struggles with finding the right balance of what to report publicly, but admits greater understanding is needed.

“The general public sees a number and they compare the number from one building to the next,” she says. “They need the whole picture before they make the assumption that this nursing home and their company is a good one, and this nursing home and this company is a bad one.”

COVID-19 Reporting Not Necessarily Representative Of Care Quality

The consensus among both providers and public health officials is that the presence of COVID-19 in a facility is not necessarily representative of the care residents are receiving or will receive.

Zach Cattell is the President at the Indiana Health Care Association, a trade organization representing long-term care facilities across Indiana.

“We have seen buildings that are five-star buildings, have had outstanding records that have been devastated frankly by the virus and have had a large number of cases and had people pass away,” he says. “The past regulatory records don’t really have a bearing on what that virus is capable of doing and where it is going to reside.”

Cattell insists long-term care facilities have nothing to hide.

“We understand the importance to report this information, and really don’t have anything to hide,” he says. “I know there’s been a lot of talk about skilled nursing facilities hiding information. What the real interest here is making sure that the data itself have integrity and make sure that it is useful and meaningful.”

While the majority of facilities are releasing data, not all are.

Mick Wildin cares for his mother who is in a long-term care facility in Greenwood. He heard things were going on in the facility before he was ever notified.

“It wasn’t really until my mom tested positive that I heard much about it. At that time they were close to 45 percent that tested positive.”

Soon after, his mother was confirmed to have COVID-19. While she ended up asymptomatic and is now now fully recovered, he wishes there had been more transparency from the start.

“I would rather know what’s going on than be kept in the dark,'' he says.

Wildin isn't alone. ISDH set up an email for caregivers not receiving information. According Indiana’s Joint Information Center (JIC), at least 22 complaints have been filed.

“Our focus is on managing and responding to emails efficiently. We do not have a breakdown of forwarded versus resolved,” the center wrote in an email.

State Health Commissioner Box admits she’s received emails directly from caregivers not receiving information.

“I can tell you that I receive emails about this,” she said in a press conference last month. “We look into every single one of those.”

The JIC declined to say if any complaints were resolved, only that they had been received and followed-up on.

WFIU/WTIU Researcher Cathy Knapp contributed to this story.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.