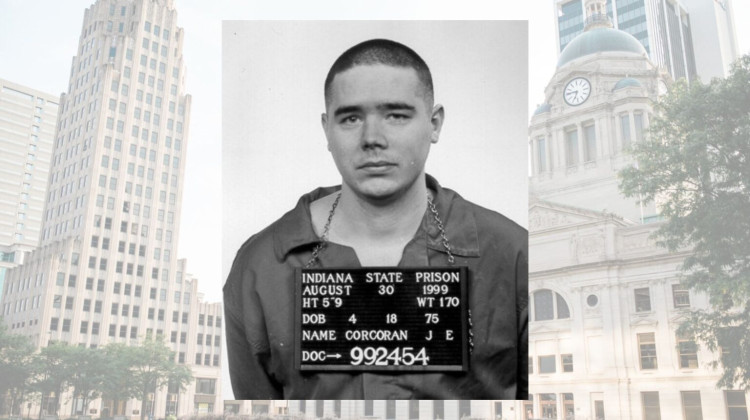

Indiana’s governor and attorney general have asked to set an execution date for Fort Wayne’s Joseph Corcoran, who was convicted in a 1997 quadruple homicide.

Courthouse photo from Allen County; Mugshot from public record; Photo illustration by Casey Smith / Indiana Capital ChronicleAfter 15 years with no executions of the eight men on Indiana’s death row, Indiana’s top elected officials filed with the Indiana Supreme Court on Wednesday to schedule an execution date for Fort Wayne’s Joseph Corcoran. He was convicted of murdering four people in 1997.

Gov. Eric Holcomb and Attorney General Todd Rokita, in a news release, said the Indiana Department of Correction (DOC) has obtained the drug necessary to carry out the death penalty.

“After years of effort, the Indiana Department of Correction has acquired a drug — pentobarbital – which can be used to carry out executions. Accordingly, I am fulfilling my duties as governor to follow the law and move forward appropriately in this matter,” Holcomb said.

Corcoran’s death would be Indiana’s first execution since 2009.

Four of the men on Indiana’s death row have exhausted all their appeals — Corcoran exhausted his appeals in 2016 — and have no other recourse, according to the Indiana Public Defender Council’s website. All eight reside in the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City.

Indiana’s officials signaled that more executions could be imminent, depending on the availability of lethal injection drugs.

“In Indiana, state law authorizes the death penalty as a means of providing justice for victims of society’s most heinous crimes and holding perpetrators accountable,” Rokita said in the release. “Further, it serves as an effective deterrent for certain potential offenders who might otherwise commit similar extreme crimes of violence. Now that the Indiana Department of Correction is prepared to carry out the lawfully imposed sentence, it’s incumbent on our justice system to immediately enable executions in our prisons to resume. Today, I am filing a motion asking the Indiana Supreme Court to set a date for the execution of Joseph Corcoran.”

Difficulty obtaining drugs

In August 2022, a DOC spokesperson confirmed to the Indiana Capital Chronicle that the agency hadn’t proceeded with any executions because of a lack of drugs: methohexital, pancuronium bromide and potassium chloride. Combined, the three drugs are used in lethal injections.

Indiana and other governments have struggled to acquire the drugs from pharmaceutical manufacturers who don’t want their products to be used in executions.

It is unclear how the state obtained the pentobarbital. The governor’s office on Wednesday declined to say where the drug was acquired, per state law.

Lawmakers made information about the source of the drugs confidential on the last day of the 2017 legislative session.

Washington, D.C. lawyer Katherine Toomey asked for information related to lethal injections in 2014 under Indiana’s Access to Public Records Act. She won the resulting lawsuit but, behind the scenes, the DOC was working with the governor’s office to devise a legislative blockade.

Lawmakers inserted a provision exempting information related to lethal injections from the state’s public records law into a lengthy budget bill. A judge then ruled for the agency. When the Indiana Supreme Court took it up, its four members — one recused himself — split, affirming the decision in 2021.

The ICC is still seeking the cost of the drug, however.

It appears the state will follow in the steps of Texas, which uses a single-drug protocol of Pentobarbital for an execution — the drug Holcomb named in his statement. Other states have looked elsewhere; earlier this year, Alabama carried out the nation’s first execution by nitrogen hypoxia.

Executions are prohibitively expensive and burdensome for prosecutors and their counties as defendants exhaust their appeals. The state can request the death penalty in cases with at least one aggravating circumstance, such as the age of the victim, multiple victims or the killing of a law enforcement officer.

No one has been added to the state’s death row since 2014.

Background on Corcoran’s case

Joseph Corcoran – then 22 — killed his brother, James Corcoran, 30; Robert Scott Turner, 32; Douglas A. Stillwell, 30; and Timothy G. Bricker, 30, on July 26, 1997. He committed the murders at the home he shared with his brother and a sister.

Joseph Corcoran told police at the time that the four men had been talking about him. He first placed his 7-year-old niece in an upstairs bedroom to protect her from the gunfire before killing the four men.

He then laid down the rifle, went to a neighbor’s house, and asked them to call the police. A search of his room and attic, to which only he had access, uncovered over 30 firearms, several munitions, explosives, guerrilla tactic military issue books, and a copy of The Turner Diaries.

Allen Superior Court Judge Fran Gull presided over the case. She is currently embroiled in controversy as a special judge in the Delphi case involving the deaths of two young girls.

Corcoran asserted an insanity defense based upon his diagnosis as having either a paranoid or schizotypal personality disorder, according to the Clark County Prosecutor’s Death Row website.

Corcoran’s mental health has been an issue over the life of the case. His conviction was overturned at least once but was later reinstated.

During the sentencing phase of the case, the jury sent a note out asking why Corcoran’s parents didn’t testify in his defense. The answer — purposely omitted from the trial — is that his parents were dead, and that Corcoran was acquitted in 1992 of their shotgun slayings.

Corcoran had an execution date set in 2005 but a federal judge granted a stay to review some of the decisions made by state courts in the case. Among the decisions that were challenged then were rulings that Corcoran was competent to waive further challenges of his sentence even though he had been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.

The case has even reached the U.S. Supreme Court on multiple occasions, including a 2010 decision to reinstate the death penalty and overturn a ruling by a lower court, according to the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette.

Corcoran can still seek clemency or a pardon in his case — an unlikely option that hasn’t been granted to a death row inmate in over a decade.

Indiana Capital Chronicle Reporter Leslie Bonilla Muñiz contributed to this story.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.