Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department officers at the Whitfield home said they believed he was experiencing “excited delirium” moments before he died. But medical experts say the previously accepted, and now debunked, diagnosis is rooted in racist stereotypes and often used by law enforcement to justify in-custody deaths.

Photos courtesy of IMPD and the Whitfield family / Illustration by Farrah AndersonWhen Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department officers responded to Herman Whitfield III’s house, he was sweating profusely, shouting and speaking strangely.

Body-worn camera footage obtained by the Whitfield family through a court order and viewed by WFYI shows the minutes after Whitfield III was taken to the hospital in the early morning hours of April 25, 2022.

“We don’t know if this is an in-custody death or he’s gonna live and it’ll just be a use of force,” Officer Jason Mitchell, who arrived at the scene after Whitfield III was taken to the hospital, is heard saying on the phone.

Later, one of the six responding IMPD officers, Dominique Clark, is heard telling Mitchell, “You know what I think about it…Honestly, I think it’s excited delirium.”

That term, “excited delirium” or “agitated delirium,” is used by law enforcement to describe people who become aggressive due to a mental illness or stimulant use. Proponents of the term say it could lead to the sudden death of detainees.

But it’s also a rejected medical diagnosis, which health care experts say misappropriates medical terminology and should not be part of the criminal justice system’s lexicon.

While it's unclear if excited delirium played a role –– direct or indirect –– in the police’s interaction with Whitfield III and his eventual death, Clark and Mitchell's brief exchange provides a glimpse into the state of policing and the kind of training that law enforcement, including IMPD officers, get.

Although excited delirium has been used to try to justify dozens of deaths at the hands of police in the U.S. — including the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis —, it is not recognized by the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases, or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

“It’s a made-up diagnosis,” said Dr. Douglas Zipes, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor emeritus at Indiana University School of Medicine, adding that the term shields law enforcement from accountability.

This has prompted some state legislatures to ban, or consider banning, the use of excited delirium as a cause of death. Others are moving to ban the term from police training materials.

Indiana is not one of them.

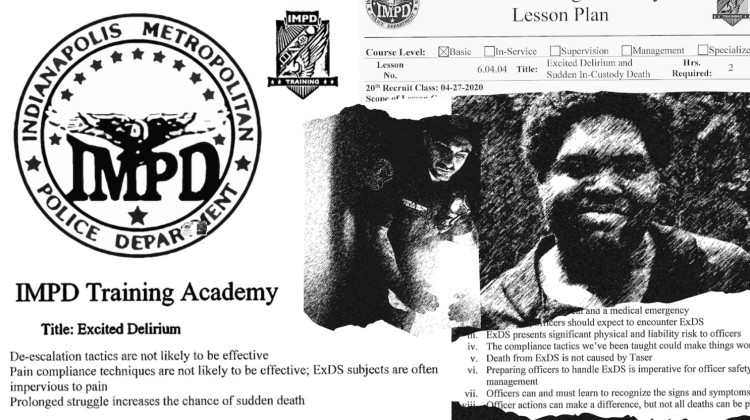

In fact, documents show that IMPD explicitly trained recruits on excited delirium and reiterated controversial statements and shaky medical theories before — and after — Whitfield III’s death.

Medical experts say the term excited delirium manipulatively draws upon legitimate medical conditions –– such as delirium, mental illness, drug intoxication and sudden cardiac arrest –– to imply that some people are predisposed to suddenly die in police custody. It also amplifies racist tropes. Some police trainings say that people going through excited delirium may be “impervious to pain” or have “superhuman strength.”

The result: studies show that in the U.S. the diagnosis disproportionately impacts Black men who die in police custody.

“I think there's probably a lot of police departments around the country that are still training on this in this way, and their training really needs to be updated,” said Joanna Naples-Mitchell, an attorney with the nonprofit Physicians for Human Rights.

Despite controversy, excited delirium is still invoked in Indiana courts

Herman Whitfield III, known by the nickname Trey, was a talented pianist and composer who emerged as a child prodigy during piano lessons in his hometown of Indianapolis.

His parents — Herman Whitfield Jr. and Gladys Whitfield — called 911 requesting help when he was going through a mental health emergency. About one hour after police arrived, Whitfield III was shocked with a Taser, physically restrained and pronounced dead.

The coroner’s office ruled 39-year-old Whitfield III’s death a homicide and further ruled he died from cardiac arrest while under law enforcement restraint. The coroner's report also noted morbid obesity and heart disease as contributing factors. And the toxicology report showed that Whitfield III had cannabinoids — THC and Delta-9 — in his system, the chemicals that cause the high of marijuana.

Nowhere did the coroner mention “excited delirium.”

Still, the diagnosis has been invoked on the scene at the Whitfield home, and two years later at the trial of two of the six responding IMPD officers who were charged with involuntary manslaughter, reckless homicide and battery in his death. (The officers were found not guilty on all charges by a Marion County jury on Dec. 6, 2024)

During the trial earlier this month, when prosecutors questioned IMPD officer Jordan Bull, one of the responding officers at the Whitfield home, Bull confirmed officers are trained on excited delirium and its risks when restraining people.

“And if you’re experiencing excited delirium, you are more likely to experience positional asphyxia?” prosecutors asked. “Yes,” Officer Bull said.

“And you’re trained on that, correct?”

“Yes,” Bull responded.

Guiding IMPD officers’ conduct are: The training they receive as recruits through the IMPD Training Academy materials; and IMPD’s general orders, which are written directives that officers use to conduct their work professionally and lawfully.

In an emailed statement to WFYI and Side Effects Public Media, IMPD said that they do not currently train officers on excited delirium and that they updated their training materials in July 2022. WFYI and Side Effects requested –– more than once –– to view the new materials but IMPD declined to provide them.

IMPD then said that they “updated General Order 8.1 in July 2022 to align with the medical community’s rejection of the term ‘excited delirium.’ However, a few older materials may still contain outdated language.”

IMPD also did not clarify whether any retraining was mandated for current officers.

“Currently, IMPD is prioritizing a complete overhaul of its training on restraint-related deaths, guided by recommendations from the Police Executive Research Forum,” IMPD said in an emailed statement. “This updated training will be introduced to the new recruit class next month and subsequently shared with all officers.”

However, documents returned in a public records request show what IMPD Academy training looked like before said updates –– and before Whitfield III’s death.

One lesson titled “Excited Delirium and Sudden In-Custody Death” mentioned that “ExDS (excited delirium syndrome) is real and is a medical emergency.” It said that the American Medical Association formally recognized the diagnosis in 2009. WFYI and Side Effects reached out to the AMA and public information officer Jennifer Sellers said that’s never been true.

IMPD’s training materials also mentioned that deaths from excited delirium are not caused by Taser use, and advised officers to use Tasers to reduce the time that patients have to struggle while experiencing excited delirium.

“The compliance tactics we’ve been taught could make things worse,” the IMPD documents, which date back to April 2020, said. “Officer actions can make a difference, but not all deaths can be prevented.”

The training materials further cited data from a 2009 American College of Emergency Physicians’ white paper that suggested that many of the deaths due to excited delirium are not preventable and that around 8% of people experiencing it will die.

But ACEP updated its guidance in 2021 and withdrew its approval of that white paper in 2023.

“ACEP’s 2009 White Paper Report on Excited Delirium Syndrome is outdated and does not align with the College’s position based on the most recent science and better understanding of the issues surrounding hyperactive delirium,” a statement posted to the chapter’s website on October 12, 2023 read.

“The term excited delirium should not be used among the wider medical and public health community, law enforcement organizations, and ACEP members acting as expert witnesses testifying in relevant civil or criminal litigation.”

Whitfield III’s death was not the only instance when law enforcement cited excited delirium.

IMPD also used the term excited delirium as an explanation for the condition of Eleanor Northington, who was having a mental health crisis at church and died after being restrained by police in 2019. Northing had a history of paranoid schizophrenia and was off her medications, according to court documents. The autopsy report did not list excited delirium as a cause of death, the family’s attorney confirmed.

Northington’s estate did not push back on the term in a civil lawsuit filed against the city of Indianapolis in 2021. But they argued how IMPD officers handled Northington while she was prone, or laying on her stomach, amounted to battery.

The attorney pointed to IMPD’s general orders, which highlighted the risk of asphyxia if people experiencing excited delirium are left in a prone position and advised officers to move individuals from that position “as soon as possible.” Northington’s estate prevailed and the city was ordered to pay them half a million dollars earlier this year.

Medical and legal experts said that even if the term is not used as an official cause of death, its ubiquity within the criminal justice system is problematic because the latest science does not support it and it puts people with mental health issues –– especially Black and brown men –– at a greater risk for excessive force by police.

‘You just don’t go out and catch excited delirium’

When the human body undergoes extreme stress due to agitation, life-threatening physiological changes can occur. For example, the heart rate can get dangerously elevated, and blood pressure can shoot up, which could cause a hemorrhagic stroke or sudden cardiac arrest. The body can also start breaking down muscle tissue at an accelerated rate releasing toxins and acids into the bloodstream, which can damage the kidneys and potentially lead to death.

The agitation can be caused by a number of things, including head trauma, drug intoxication, psychosis or other mental illnesses.

But “excited delirium” is not one of them, said Dr. Kimberly Brown, a physician in Memphis with the American Academy of Emergency Medicine.

“There's someone who is in an agitated state or having those types of reactions because of some other underlying thing, not, ‘They have excited delirium.’ You just don't go outside and catch excited delirium. There's something else that's deeper there,” Brown said.

Other experts say the term is a catch-all phrase, shifting the focus from other contributing factors or causes of death, including excessive use of force or improper restraint by law enforcement.

“It absolves [law enforcement] of any responsibility for the person's death,” Justin Mazzola, a researcher with Amnesty International USA, said. “When you list something that's kind of amorphous in general, like excited delirium, it doesn't look at actions by law enforcement that may have contributed or caused the individual's death specifically.”

One study in 2012 authored by Dr. Zipes with IU School of Medicine found that Taser electrical shocks to the chest can cause cardiac arrest and sudden death. The study looked at animal cases and analyzed detailed clinical records of eight people from across the country who went into cardiac arrest shortly after being shocked by a Taser. The paper argued that while the overall risk may be low, the exact incidence is unknown due to lack of mandatory reporting and a national database in the U.S.

“I remember so vividly one particular case where an individual was very agitated and was delirious for some hours prior to the Taser application, was shot by the Taser and in 30 seconds had cardiac arrest,” Zipes told WFYI and Side Effects Public Media.

Zipes said that attributing a Taser-related death to excited delirium requires assuming that the excited delirium itself caused the cardiac arrest at the exact moment of the Taser shock, which he considers an improbable coincidence.

But Taser manufacturer Axon, formerly Taser International, said in a statement to WFYI and Side Effects that Tasers are safe and effective.

“TASER devices are intended to be less-lethal alternatives to firearms and are designed to save lives. They are one of the most studied, safe and effective means of quickly stopping a threat,” Axon’s statement said.

Naples-Mitchell with Physicians for Human Rights said it’s common for people who work as experts for hire to spread the word about excited delirium — shifting blame away from Tasers and law enforcement to the subjects themselves.

“This is a term that has a very powerful lobby behind it,” Naples-Mitchell said.

One of the expert witnesses that the defense brought in during the Whitfield III jury trial was Mark Kroll, a biomedical scientist with a Ph.D in electrical engineering.

Kroll refuted claims that the Taser had any role to play in Whitfield III’s death.

He has also been a compensated board member for Axon until 2024.

Kroll often testifies in cases where police officers use Tasers on subjects. According to a 2017 Reuters investigation, Kroll had previously likened Tasers to therapy for people gripped by excited delirium.

Mazzola and other advocates said IMPD should review its policies regarding Taser use and excited delirium, especially in the wake of the term being invoked by on-the-scene officers and during the trial in the death of Whitfield III.

‘Treating health crises as health crises’

In the U.S. in 2024, the response to mental health crises continues to rely primarily on law enforcement, with limited access to round-the-clock mental health support or co-responders. This heightens the risk for people with mental illness –– increasing their chances of traumatization, arrest, injury and death –– and puts officers in tough and perilous situations on the job.

Police officers receive classroom and simulated training on responding to mental health crises, but the amount of real-life experience they have with such emergencies before facing high-pressure situations on the job varies widely.

“It’s luck of the draw for on-the-job training,” IMPD Defense Tactics and Deescalation training supervisor David Young said during the Whitfield III trial.

And many medical experts and advocates appreciate the complexity of the situation.

Dr. Brown with AAEM said she understands the need for police departments to describe to their officers the different scenarios they may encounter when responding to mental health crises. But using neutral terminology and science-based information that don’t reinforce racist images and conjure fear in officers is key, she said.

“I think that they're trying to say, ‘When you see someone demonstrating these symptoms, it is a medical emergency’. That would be the more proper way to say it. But I appreciate the fact that there is some training that's there,” Brown added.

Ultimately, it’s about creating a system where law enforcement officers are not the first or only responders to mental health emergencies –– something that cities, including Indianapolis, started to do, on varying scales.

“This is about treating health crises as health crises, and not criminalizing the response,” said Naples-Mitchel. “This will prevent a lot of deaths.”

Farrah Anderson is an investigative health reporter at WFYI and Side Effects Public Media. She can be reached at fanderson@wfyi.org.

Farah Yousry is the managing editor of Side Effects Public Media at WFYI in Indianapolis. She can be reached at fyousry@wfyi.org.

Side Effects Public Media is a health reporting collaboration based at WFYI in Indianapolis. We partner with NPR stations across the Midwest and surrounding areas — including KBIA and KCUR in Missouri, Iowa Public Radio, Ideastream in Ohio and WFPL in Kentucky.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.