On Monday, April 6, an inmate at Indiana’s Plainfield Correctional Facility stayed up late. From his bunk, he composed two messages. In the first, he told his son that he loves him, that he’s proud of him.

In the second message, he told his wife he was scared. “I can tell you right now, nearly 100% certainty, that I am going to get this virus,” he wrote. The man’s wife says he suffers from lung disease, which could increase the chances of complications from COVID-19.

“I just need you to know how sorry I am for not being there … during these scary uncertain times,” he wrote. “If I don’t getta come home please always know that you are and always will be the love of my life.”

Two days later, the man told his wife that for the first time, prison staff took the temperatures of the men in his quarters. Some of the prisoners had fevers, including one who slept right next to him, but were kept in the dorm with dozens of other men. ”He is about 3 ft. from me right now,” he wrote. He wrote back after midnight to tell his wife the prisoners with fevers were finally removed.

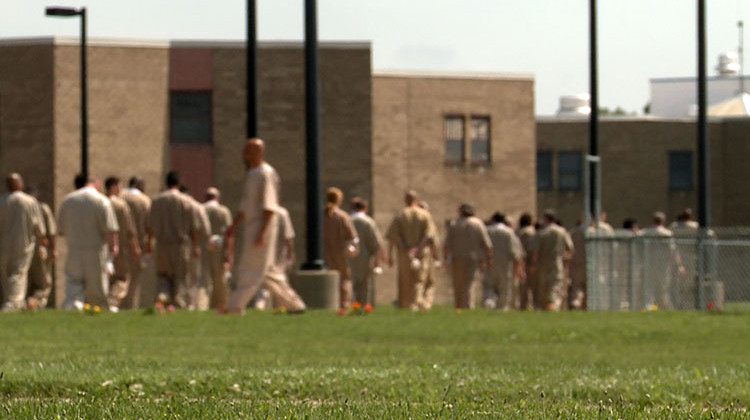

Outside of correctional settings, federal, state and local officials are urging people to hunker down. People are staying at least six feet apart, wearing masks and regularly washing or sanitizing their hands, along with surfaces they touch.

The Indiana Department of Correction says it is taking measures to prevent the spread of coronavirus among the more than 26,000 inmates housed in the state’s 21 facilities. That includes supplying hand sanitizer to inmates and isolating anyone who exhibits COVID symptoms.

But accounts from inmates and their relatives contradict the agency’s claims. They say inmates are kept in tight quarters where they are unable to wash or sanitize their hands, or clean surfaces that could harbor the virus. And they say prison staff aren’t taking proper care to prevent the spread of the virus.

“That’s illustrative of what’s happening across the country in county jails and departments of corrections,” says Lauren-Brooke Eisen of the Brennan Center for Justice in New York. Nationally, more than 1,300 prisoners have been infected, according to a recent analysis from the New York Times, and dozens have died.

Eisen isn’t surprised that the virus has spread so quickly in American jails and prisons: “They really are petri dishes for transmission of diseases such as COVID-19.”

In Indiana, 23 inmates in six prisons have tested positive for COVID-19, along with 33 staffers. The state, which only takes questions via email, did not answer when asked how many people had been tested.

Side Effects spoke with family members of prisoners in multiple facilities, including the Plainfield Correctional Facility, the Branchville Correctional Facility, and the Heritage Trail Correctional Facility -- all three of which have confirmed COVID-19 cases. We heard recordings of prisoners speaking with their wives about their experiences -- and even spoke on the phone with an inmate in the Indiana Women’s Prison. (Side Effects is omitting the names of inmates and the last names of inmate family members due to their concerns that the inmates would be punished for speaking out.)

All of them expressed fear and frustration.

The Plainfield prisoner’s wife, Lisa, worries about her husband. “I am so terrified, and I feel helpless. I don’t know what to do,” she told Side Effects.

Her husband went to prison a year ago for driving on a suspended license, theft and resisting arrest. He could be released as early as June 2021.

“Yes, they committed a crime and they were sentenced,” she says. “But they weren’t sentenced to death.”

Tight quarters, few supplies

On April 9, Side Effects received a call from a prisoner at the Indiana Women’s Prison in Indianapolis, along with three other calls from people whose loved ones reside there.

The prison went into lockdown last week, they said. Three or four women are stuck in each room, with no access to cleaning supplies, running water or hand sanitizer.

“We have to beat a door down to use the restrooms,” said the inmate, who was sentenced after her dependent died from neglect. The unit holds dozens of people, she said, and is currently staffed by one officer who unlocks the rooms one at a time.

“People scream and bang on doors all day,” she said. “We’re scared to drink water because we’ll have to go to the bathroom.”

The rooms are cramped. “I can lay on my bed and touch my bunkie without putting my arm out,” she said. And she and her bunkmates are worried they will contract the virus from the prison guards, who rarely wear masks or gloves.

“We are so scared in here,” she said. “It’s just really nerve-wracking.”

Prisoners at other facilities and their family members expressed similar concerns.

“The only thing they’ve done is brought us a bar of soap two weeks ago,” the Plainfield prisoner told his wife in a phone call that she recorded and made available to Side Effects. Despite measures laid out in the corrections agency's Preparedness and Response Plan, hand sanitizer is not available to the inmates, unless they purchase it through the commissary, according to multiple inmate accounts.

And social distancing is impossible, they say. A prisoner at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City described a crowded chow line and cafeteria.

“They will not let us practice social distancing,” he said, according to a recording she made. “There’s not enough room between the tables. You’re always being scraped up against -- there’s just no room.”

A man in a different part of the Plainfield prison also said men in his quarters were not immediately quarantined when it was discovered they had fevers.

Guidance put out by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which the state says it is following, says prisoners exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms, including fever, should be isolated.

The same CDC guidelines highlight the importance of social distancing. But in a call with his wife, the second Plainfield prisoner said that, as in the women’s prison, he would touch another inmate if he extended his arm.

“It’s a breeding ground for infections and viruses,” he told her, according to her recording of the call. “We’ve got reason to be scared for our lives.” Sentenced for a robbery, his earliest possible release date is in 2022.

His wife, who asked to be identified only by her middle name, Nicole, said her husband tried to make a tent with blankets to protect himself, but a guard told him to take it down.

“I would normally tell my husband to comply,” Nicole said. “But at this point, I told him, ‘Absolutely not. Do not pull your blankets down. If you get a write-up, we’ll deal with it.’”

State policy

On April 9, Chief Medical Officer Dr. Kristen Dauss, posted a video on the corrections agency’s response to the virus. “All that we’ve done and continue to do is protect the offenders at our correctional facilities as well as our dedicated staff working for the Department of Correction,” she said.

Staff members who are sick are not allowed to work, she said. Facilities are being cleaned, offenders are being monitored for signs of illness and floors now have markers to help with social distancing. “We continually resupply soap and hand sanitizer at all correctional facilities,” she said.

Family members who saw the video said it made them angry.

The agency declined an interview request to discuss safety measures and prisoner complaints. In an email response to follow-up questions, it maintained that facilities follow guidelines laid out by the CDC and the Department of Correction.

Reducing the population

The Brennan Center, a nonpartisan policy institute that advocates to end mass incarceration, has sent letters to governors across the country, urging them to release prisoners who don’t pose a threat to public safety. “It’s necessary to curb the spread of coronavirus behind bars in this country,” says Eisen.

She points out that neighboring states Ohio and Kentucky are set to release hundreds of prisoners in response to the pandemic.

Indiana officials, including Gov. Eric Holcomb, acknowledge that jails and prisons could be especially vulnerable to the spread of coronavirus, and that reducing the number of inmates could slow it down.

The Department of Correction has stated that it has compiled lists of prisoners who could potentially be released early, such as non-violent offenders and the elderly. Decisions about those individuals now rest with trial courts.

The ACLU of Indiana recently petitioned the state supreme court, asking it to order lower courts to consider early release for certain prisoners. The ACLU said the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution “prohibits state officials from acting with deliberate indifference to a convicted prisoner’s serious medical needs.”

On Wednesday, the high court denied the ACLU’s petition. The state did not answer questions about how many prisoners had been recently released in the effort to reduce spread of the disease.

Meanwhile, prisoners remain in tight quarters, worried about the virus. They and their families are frustrated.

“They’ve done the absolute bare minimum on preventing it,” said Nicole. “That’s deliberate indifference in my book. Nobody’s doing anything.” She added that even if her husband can’t get out, reducing the population would help those who remain in the prison.

“They need to start letting people out of here that are sick,” said the first Plainfield prisoner in a recorded call with his wife, Lisa. “There are a lot of sick people in here.”

“They’re not protecting these men,” said Lisa. “It’s just not right.”

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a news collaborative covering public health. Jake Harper can be reached at jharper@wfyi.org.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.