Have a news tip for WFYI's education team? Share it here.

When 37-year-old Laurin Perry graduated from her rural Indiana high school, she knew she was supposed to go to college.

A generation of U.S. teenagers got the same message — that they should strive to earn a bachelor’s degree even if they didn’t know what subject they wanted to study or what career they would pursue.

Perry went to Purdue University, but she didn’t graduate. Now, she owns a construction company with her husband. A college degree now seems unnecessary.

So when Perry talks about her three teenage children her perspective has shifted.

“If they want to go to college, I'm very open to that,” Perry said, “but I'm not going to be a person to force them to go.”

That outlook is one reason why Perry and her husband, who live in rural southern Indiana, send their children to a nearby school district that’s gone all-in on career and technical education.

Indiana is at a moment of transition as students, parents and state policymakers question the long-held assumption that four-year college is the primary route to a middle-class life. The college-going rate is down across the country amid increasing skepticism about four-year college degrees.

In Indiana, the rate of students going straight to college from high school is stagnant after several years of decline. In rural counties, the drop is particularly sharp — by 21% between 2017 and 2022.

Meanwhile, enthusiasm is growing for career and technical education, once known as vocational education. When the think tank Populace surveyed Americans about K-12 education in 2022, people ranked preparing students for careers as their sixth priority. By contrast, preparing students for college was low on the list.

More Indiana high schoolers are pursuing career and technical education, in part as a result of state policies that encourage the focus. In the class of 2023, nearly 40 percent of Indiana students concentrated in a career — taking at least three classes in one field. And more than 80 percent took at least one course in a career pathway.

In interviews with WFYI, Indiana high school students, recent graduates, parents and educators seldom say that going to a four-year college is a mistake. Instead, many are skeptical of the idea that everyone should go to college.

U.S. students and parents don’t want to use four-year college as “the most expensive career exploration opportunity they can find,” said Dan Hinderliter, associate director of state policy at Advance CTE, a national association that represents state leaders.

For some students, career and technical education helps prepare them for skilled jobs without going to college, he said. For others, it’s a way to explore careers before committing.

“They want to be able to figure out what their career future could be — and what they want it to look like before they make those big expensive decisions,” Hinderliter said.

Indiana high schools are taking heed. Schools that once pushed all students to go to college are now working to give students access to other options, like trade programs.

A rural school leading the way

Shoals Community Schools, where Perry’s children attend, is in Martin County, a rural part of southern Indiana where educational attainment was already low. Only about 13 percent of adults have bachelor’s degrees. And the proportion of high schoolers who head straight to college has been declining.

Educators in Shoals say that in a place where many graduates won’t go to college it’s particularly important for the high school to offer good career training.

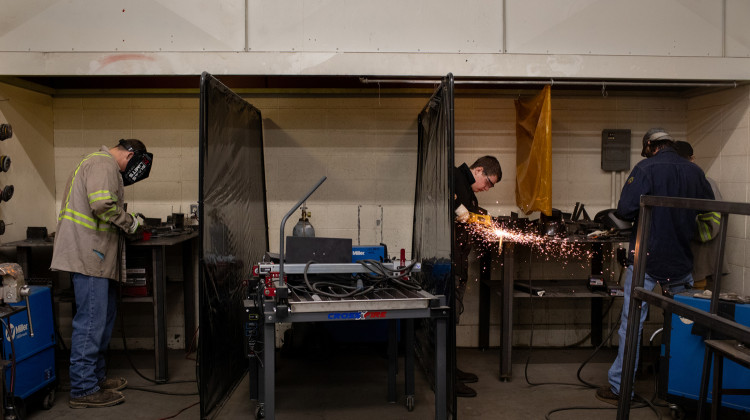

Shoals students explore career options in middle school and choose a pathway in high school. The district offers 11 focus areas, including healthcare, construction and agriculture.

Shoals senior Isiah Wininger thinks that if he hadn’t taken career classes in high school, he would be planning to enroll in college after graduation. But taking construction helped him realize that he likes hands-on work more than sitting behind a desk. Now, Isiah aims to become a diesel mechanic — a job he’s really excited about.

Diesel mechanics make median wages of about $59,000 per year in the U.S., according to federal data. That’s significantly less than what workers with bachelor's typically make. But it’s about $12,000 above the median wages for high school educated workers in general.

“Getting a little bit dirty don't bother me,” Isiah said. “Pretty much every trade that I know is in high demand.”

‘CTE for all’

Research from the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce shows that about 40 percent of “good jobs” don’t require a bachelor’s degree. Many of those jobs require education or training beyond high school like certificates or associate degrees.

For young people without training beyond a high school diploma, the pool of good jobs is increasingly limited and pay varies widely by industry.

Director of the Georgetown center Jeff Strohl warns against making career and technical education the new universal standard.

"We don't want to be guilty — as we were guilty with ‘college for all’ — to say ‘CTE for all,’ “ Strohl said. “The fact of the matter is, there's not enough jobs in the middle-skills and high school economy to support middle-class earnings for every high school student.”

Advocates for career and technical education argue that it complements — rather than competes with — higher education. For the class of 2023, over half of Indiana students who concentrated in a career field earned college credit while in high school.

As a student at Shoals, Zane Lake, now 22, took advantage of career training and college preparatory classes. Lake planned to pursue a bachelor’s in mechanical engineering. But when he enrolled at Vincennes University, he decided at the last-minute to pursue a two-year program in precision machining. He said the program appealed to him because it was more hands on.

Now, Lake works in a machine shop building custom parts.

“I like being able to take a block of metal or plastic or whatever and making it into a part,” Lake said, “then being able to watch it work and do what it was intended to do.”

For some students, learning about career options while in high school offers a vision of how to make a good living without a degree.

When Collin Hampton, 22, was younger, he thought the only way to avoid a job in manufacturing or mining was to go to college. But as a teenager, he learned about other options.

During his high school construction class he helped pour a concrete walking path. He liked it so much that he and his father started a concrete company.

Hampton says he wouldn’t have considered this career if it weren’t for his high school experience. And he wants other students to have the same kind of exposure.

“I think you need to get experience and hands on and figure out what you want to do because you may not like it when you actually get into it,” Hampton said. “Then if it is a college degree, you waste a lot of money in college and you don't like it.”

This story was supported by the Higher Education Media Fellowship at the Institute for Citizens & Scholars.

Contact WFYI education reporter Dylan Peers McCoy at dmccoy@wfyi.org.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.