Frankfort teacher Anne Lanum works with English learner students.

The English learner population is growing across the Midwest, as more immigrants settle in smaller towns, and Indiana is currently seeing an increase of students needing to learn English at a higher rate than the rest of the country.

While most schools struggle to meet the needs of students who don’t speak English, this challenge is especially obvious in rural school districts, where enrollment is decreasing and resources are tight.

Madeline Mavrogordato, an assistant professor in the College of Education at Michigan State University, conducts research on English learners. She said rural districts do struggle, but they can also adapt more quickly than large districts.

“So I think one of the things that’s amazing about working in a school district like that, is they tend to be smaller to begin with. So the power you have to actually impact change in a district like that is incredible,” Mavrogordato said.

In Indiana, the rural district Community Schools of Frankfort is also the district with the highest percentage of English learners in the state. Its need for English learner resources is also one of the highest in the state, and it is an example of how many schools are struggling to keep up with the growth of English learners.

Changing Attitudes to Effectively Teach

Frankfort is a small town in central Indiana with a little more than 16,000 people. Over the last few decades, as more factory jobs became available, more Latino families moved there.

Anne Lanum started as a elementary school teacher in the Frankfort school district, 16 years ago. Over that time, the number of her students with English learning needs grew from 20 to 90 percent. In the beginning of this boom, Lanum says negative attitudes about the population change in the community reached the schools.

“At that time they weren’t really accepted, people didn’t want them at the other schools,” Lanum said.

She said the community is more comfortable now. But she and other teachers said other challenges are harder to overcome, including the student to teacher ratio.

Frankfort has the largest percentage of English learning students in the state, 800 students in a small district. But it only has eight teachers, and that team said they’re always trying to catch up.

After seeing the negative attitudes toward Latino students, Lanum decided two years ago to get her English learner certification and switch jobs. She’s now one of those eight teachers split among the hundreds of kids needing her specified instruction.

She said it’s been a tough transition, because these students are not the district’s top priority. For example, Lanum meets with more than 200 kids at one elementary school, but she doesn’t have her own classroom.

“If there’s a room that has to go, it’s my room and I just have to find a space,” she said. “I have to find a breezeway or a corner to teach kids.”

Other teachers said they get pulled away from working with English learning students to proctor ISTEP+ exams or do lunch duty. And they all said the schools need more dedicated, certified EL teachers. But Frankfort’s Director of English Learning, Lori North, says that’s a tough ask right now.

“We had teacher cuts this year so it’s really hard for me to go and say ‘I need more EL teachers’ when they’re cutting general education teachers,” North said.

They all said the attitudes have gotten better in the community and in the schools toward these students. Principals and other administrators are starting to understand why English learning classes are important for these students to succeed in the rest of their classes.

“Everyone's an English Learner Teacher"

The situation for the Frankfort schools is typical for most schools with high English learner populations.

Right now in Frankfort, there is typically one EL teacher per school that has hundreds of students needing their services. This one teacher spends the days helping classroom teachers co-teach, a combination of pull out sessions with small groups and large class sessions.

Teachers in Frankfort said this is not ideal because students aren’t getting enough uninterrupted, individual instruction.

Mavrogordato said that’s a common problem everywhere, and if schools that aren’t able to hire more English learner teachers want to better serve the kids there is a more plausible solution.

“If you’re lucky kids are going to get pulled out of class maybe two days, three days a week to receive services,” Mavrogordato said. “But the other six hours of the day across five days a week, they’re with general education teachers. So if the general education teachers have not received training or professional development to help them address the linguistic and cultural needs of English language learners, it’s going to be an uphill battle.”

The teachers in Frankfort are trying to employ this tactic in their schools. Melissa Griggs is one the English learner teachers and also coaches classroom teachers on tactics to use in the classroom.

“So much is suffering because they’re not learning grade level content if they’re not learning the language,” Griggs said. “But I think that’s also where we do a great job of informing the teachers and giving them strategies on how to help too.”

And Griggs said, in a district where up to 50 percent of the class could not understand what the teacher is saying, every teacher becomes an English learning teacher.

“They Just Need Language"

For North, the most frustrating part of not having enough staff and training to help students learn English is that she knows that these students are smart.

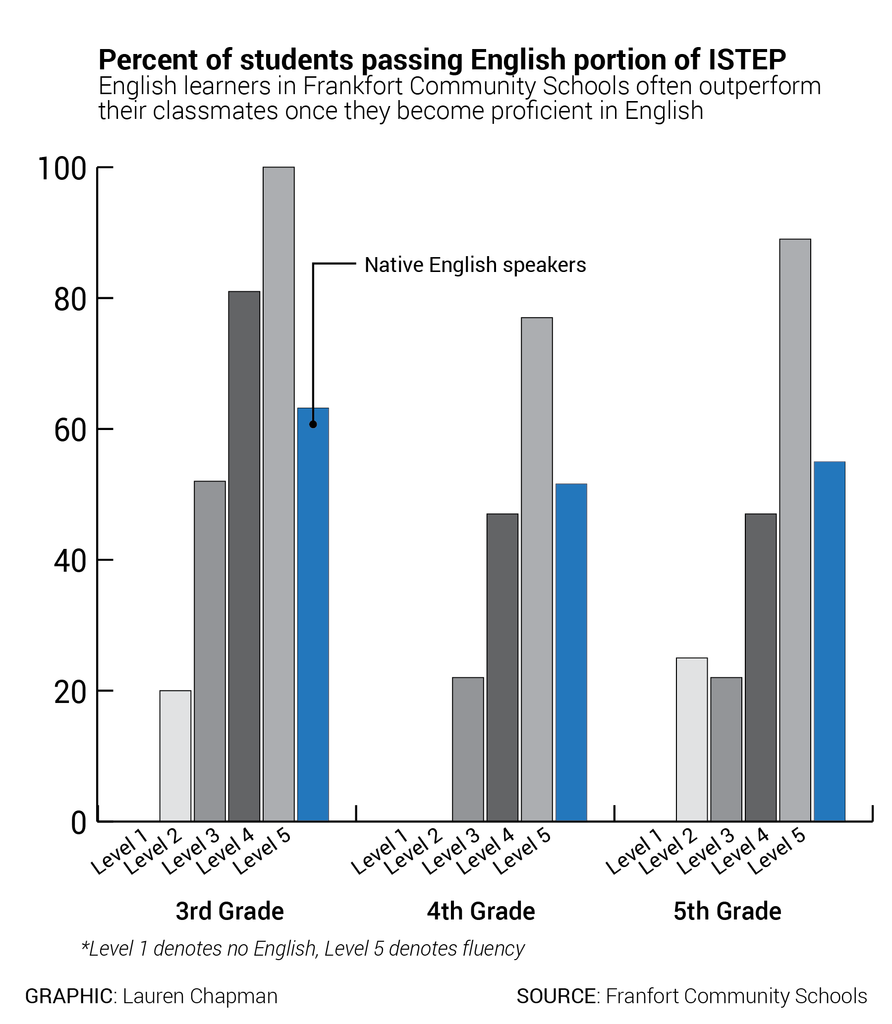

The Community Schools of Frankfort received Ds on the state’s A-F system the last three years. English learners must take the ISTEP+, but they cannot have it translated. This means most English learners fail the test, and with a third of students in the district learning the language, ISTEP+ scores are often low.

North said the district doesn’t put pressure on her team to perform better, but the teachers are disappointed by this situation.

“I think we feel pressure in our own buildings because we feel tired of failing,” North said. “We’re tired of working so hard, but we don’t get the numbers.”

But once the English learners master the language, most are strong academically.

“They just need language,” North said. “Once they have language, in many ways, they outperform the general population.”

Because the school district is tight on money for everything, North said she can’t ask for too much for the English learners. She has grant money that she wants to use to get classroom teachers EL certified. She says if more teachers know how to help the kids, the better it is off everyone.

“They just deserve every opportunity they can give them,” North said. “I know my EL teachers work really hard to do that, but it never feels like enough. I think that’s what we feel like, we’re eight strong. Like we’re doing our best, we’re doing the very best we can but is that enough?”

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.