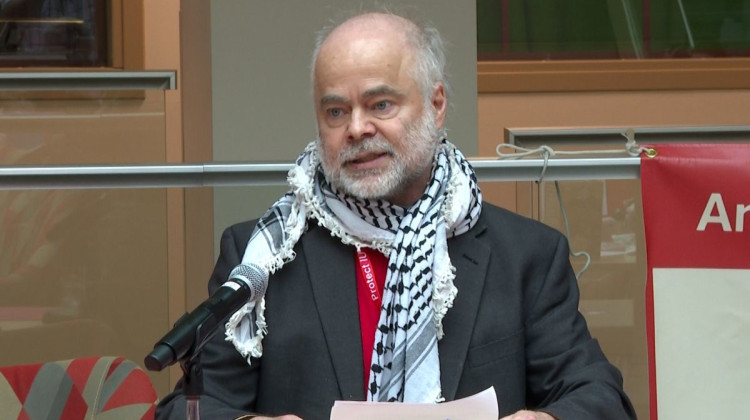

Victory College Prep in Indianapolis is using some of its federal pandemic relief funding to add more teachers to classrooms to help students catch up academically.

(Dylan Peers McCoy/WFYI)At Victory College Prep, leaders face a challenge that used to be unusual in education: deciding how to spend a deluge of money. The school was awarded more than $10 million in federal coronavirus aid — nearly the whole budget for a typical year.

The temporary federal funding, part of two stimulus bills passed last December and this March, is supposed to help schools make up for the tumultuous and uneven education that children got during the pandemic. Indiana schools will get nearly $2.6 billion, targeted to those that serve more low-income students. Nearly 90 percent of students at Victory come from low-income families.

The money offers an unusual test of whether spending more on education will improve outcomes for children.

“Unprecedented financial resources offer schools the unique opportunity ahead to increase access and outcomes for students," said Indiana Secretary of Education Katie Jenner at a meeting with state lawmakers last month.

Jenner said that federal aid and new state money could help make education better for children of color and students from low-income families.

But the test is imperfect because the funding is temporary. Superintendents and school boards hesitate to spend it on ongoing expenses — like raises for teachers or new staff — even if those areas are the best way to improve.

“If you really want to make an impact on student learning, you're not going to tell schools that they can change the way they operate for three years, you're going to tell them they can change the way they operate for the next 30,” said Ryan Gall, the executive director of Victory, a 1,000-student charter school in Indianapolis.

It remains unclear exactly how Indiana schools are spending most of the money. But many are using federal aid for one-off expenses, like building improvements or new technology. Instead of giving teachers and staff raises, they are paying them bonuses for the extra work they have done during the pandemic.

A growing body of research is fairly clear that spending more on education generally improves outcomes for students, including higher test scores and graduation rates. How schools spend the money may be constrained because it is temporary. But it is far better for school leaders to have the choices that a large infusion of cash offers, said Daniel Kreisman, an associate professor of economics at Georgia State University.

“It's really good to see the federal government react quickly and forcefully in this scenario,” Kreisman said. “Right now, things are extremely bad. So thinking too far in the future is not necessarily as important as saying, ‘we have some real gaps we need to plug today.’”

Schools are also facing unique challenges. Students are in the third academic year disrupted by COVID. Just a few weeks in, many Indiana schools have been forced to shut down in-person instruction for classes, grades or entire buildings amid record-breaking cases of COVID-19 and widespread quarantines. Research shows the pandemic has taken an academic toll on students.

At Victory, leaders won’t use the aid to boost salaries because they don’t want to cut pay when it runs out, Gall said. However, even though the money is temporary, the school will spend nearly a third of all the federal pandemic aid it has received on new staff members, including 18 teachers.

“Is it sustainable? No,” Gall said. But “I believe that I can make a significant impact on student learning and student outcomes for three consecutive years. If I do that, I'm going to change the whole trajectory of my school.”

The federal funding is already transforming Victory. The building doesn’t have space for smaller class sizes, so instead, Gall embraced co-teaching. Many classes at the school now have two teachers.

A temporary infusion of money

Two weeks into the year, about two dozen students were in seventh-grade math. At the front of the room, Samuel Lamkin wrote fractions on the white board, explaining how to cross-multiply and divide them.

As class tackled equations, Lamkin and co-teacher Rahul Jyoti roamed among the tables, pressing students to explain their solutions or prompting them on the next steps.

With two teachers in the classroom, they can check in with students more quickly, and it’s less likely students spend the class practicing the wrong way to solve a problem, Jyoti said. That’s especially important now after months of remote schooling.

“It's gonna take a lot of time to get them caught up,” Jyoti said. “But I think that feedback can help.”

The two teachers, who have both been at Victory for more than a decade, also plan lessons, grade homework, and go to training together. They not only discuss how students are doing but also critique each other, sometimes tweaking lessons between classes.

“I think the feedback we give each other throughout the course of the day is the most benefit,” Lamkin said.

When the federal funding dries up, Victory may have to change the approach, cutting back on the number of teachers. And that could force the school to make painful cuts.

But Gall believes that it is worth it, in part because he doesn’t think any alternative would be as valuable for students.

“What's the trade off? I buy a million laptops, I buy brand new furniture, I put a new coat of paint on my building,” he said.

“This is our strategy and our model for the next three years,” Gall added. “In three years, if the money is not there, we'll reevaluate.”

Because most schools will get significantly less federal aid per student than Victory, it will likely be less transformative no matter how they spend it.

President of the Indiana PTA Rachel Burke said for many schools, the money will be used to make up for years of underfunding. They will use it to replace out-of-date technology, books and other materials for instruction.

It makes sense for schools to hire staff to help with needs caused by the pandemic, such as new counselors and social workers, Burke said. But she said schools should avoid artificially inflating salaries or making class sizes smaller in a way that’s not sustainable.

“If you're going to make the argument that we’re going to find out whether or not extra money is what is needed in public education, then you need to make that a long term stream, so that the money can be used in long term ways,” Burke said.

Contact WFYI education reporter Dylan Peers McCoy at dmccoy@wfyi.org. Follow on Twitter: @dylanpmccoy.

DONATE

DONATE

View More Articles

View More Articles

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.