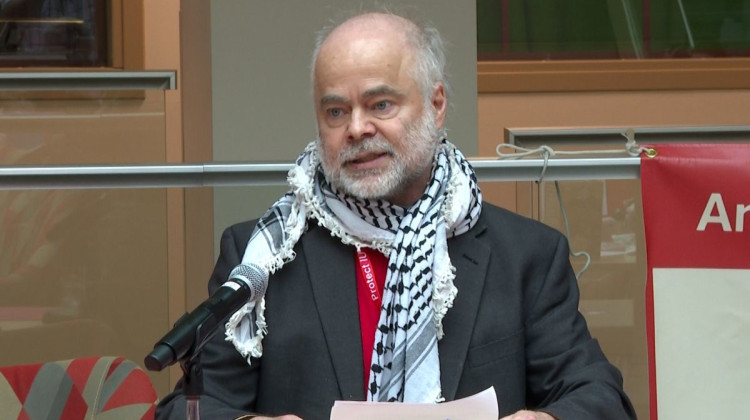

Ayana Wilson-Coles is one of two classroom teacher on the new ISTEP+ panel that teaches a grade where students take ISTEP+. The panel is tasked with re-writing the state assessment, and meets for the first time May 24.

Peter Balonon-Rosen/IPBSThe new ISTEP+ panel tasked with re-writing the state assessment is established and will meet for the first time May 24. A majority of the panel’s members are teachers, principals and superintendents who have seen issues with the test first hand and want to see it change in ways that help teachers in the classroom and doesn’t marginalize certain groups of students.

As we’ve reported, legislation passed during the 2015 establishes a panel of educators, school administrators, parents, lawmakers and other stakeholders.

Legislation mandates the group must issue a report to the legislature by December. This report will guide legislative action in the 2017 session. The state’s current testing contract with Pearson expires after the 2017 administration of the test.

Of the 23 people serving on the panel, 12 are educators currently working in school districts (teachers, principals and superintendents). These Educators say their goals for the re-write are informed by their work in their classrooms.

The focus on ISTEP+ in the classroom

One thing many educators have long criticized of the ISTEP+ is its prominence on a day to day basis in the classroom. Few teachers use it as a tool to gauge where students are academically. It’s true service is as a measuring instrument for the state, and educators have said that it looms on the minds of both teachers and students all year.

Ayana Wilson-Coles is a third grade teacher at Eagle Creek Elementary School in Pike Township. She’s one of the two members of the ISTEP+ panel that teaches a grade that takes the test.

“The second half of the school year, starting in January, we are trying to prepare our kids for the test.”

This is one of the major issues Wilson-Coles wants to address: how much she has to prioritize preparing for ISTEP+. She says during second semester she spends a lot of instruction time making sure kids are familiar with the technology, have strategies for doing well on multiple choice and understand how the time constraints will work. She says her students feel pressure to do well.

“I had a lot of kids this past year, when we took the first [installment of the] ISTEP+, break down and cry,” she says. And once they are upset, they had trouble finishing the test. “It’s not that they didn’t know what to do, I couldn’t help them, and they were frustrated and they just cried. There was nothing I could do to make them finish the test.”

And because she’s making sure the kids are prepared for the format of the test, she thinks other educational opportunities are lost. She says if the ISTEP+ didn’t have such high stakes, her classroom could be a different place.

“The mood in my classroom would be different. My kids feel my pressure as much as I try to hide it, they feel it,” she says. “I feel like I probably said ISTEP+ every week since January and at least ten times a week. I feel like my classroom would be different if I was just teaching.”

One way to change the classroom culture ISTEP+ creates is by making sure the assessment is a tool in addition to a test. But what does that mean?

The update to No Child Left Behind, called the Every Student Succeeds Act, allows for the required annual assessment to be broken up throughout the year. So rather than preparing all year for one, long test that carries so much weight, it could be given in small chunks, over two semesters.

Panel member Lynne Stallings would see that as a positive change. Stallings is an academic, and she is also the only parent on the panel. She has two kids in the Muncie school system and is a professor at Ball State, where she trains teachers who want to teach English learners.

For her, passing ISTEP+ should be a tool that tells teachers how students are progressing.

“It just felt like during this ISTEP+ time, why are we having to go back to do things we’ve already proven,” Stallings says.

The panel could suggest that the test be taken in shorter versions that test content areas as students complete them in class.

Panel member and Bateseville Schools Superintendent Jim Roberts agrees. He says that would help teachers see student progress.

“They don’t have the opportunity to really use the information from an assessment to make change and drive instruction.”

Keeping Accountability Consistent

A lot of the complaints about our current testing culture have to do with the high stakes places around them. A teacher’s evaluation is partly based on his/her student’s ISTEP+ scores. And ISTEP+ scores are currently the main factor in how elementary and middle schools receive their A-F grade. The state intervenes when a school has failing grades multiple years in a row, and responsibility to turn the school around can involve outside companies or cost the district money.

This is why teachers like Wilson-Coles say there is always a lot of pressure to do well on the test – it affects a lot of important things. And the new ESSA law also allows for accountability systems to be changed to include more than test scores.

The state is already moving in this direction. The State Board of Education recently passed a growth model that will be used when calculating the grades, so a school still gets positive points for students who improve their scores, whether they are passing or not.

The panel will be able to decide another important part of the new accountability system, which is how to reward schools for providing a positive culture and environment.

Bateseville Superintendent Roberts says, whatever this panel decides, the decisions need to last for a long time.

“That’s a part of the problem I have seen over the last few years. I am going to call ISTEP+ a game to use an analogy, but the game we’re playing the rules keep changing.”

State standards and accountability systems have changed a number of times. In the last five year, schools have had to switch their academic standards three times, administer vastly different assessments created by two different vendors and learn a new accountability system.

Roberts says no school can be expected to perform well and grow when the benchmarks they must meet are always changing.

“All of these pieces are moving targets that are hard for us to hit,” Roberts says. “First of all, we just need to get into a situation where we have consistency– the standards we are shooting for and how we’re assessing whether our students are meeting those standards.”

“What is a stoop?" And other questions on equity

Teacher Wilson-Coles works in a school with mostly black and Latino students, and says the English/ Language Arts portion of the test can be a struggle.

“If you have children who are English learners or even African-American children who speak I call ‘African-American vernacular English’ who haven’t acquired standard English all the way then they’re not going to do as well, because that’s not their first language.”

Right now, English learners must take the ISTEP+ in English. They can have a teacher read them the questions, but none of the test is written or administered in their native language, meaning they often don’t score well even if they know the content, because they don’t understand the questions.

Stallings, who teaches EL teachers and is the only parent on the panel, says she wants to offer insight from her professional experience.

“Hopefully we can find a test and a format that is equitable across the state, recognizing there are different communities that have different needs,” Stallings says.

And Wilson-Coles says there are other, more subtle ways the test is biased toward certain students.

She recalls a specific reading passage from the ISTEP+ one year, that mentioned a ‘stoop’ in the story, which confused her kids.

“In Indianapolis, my kids don’t know what a stoop is. Whereas kids in New York know what a stoop is, so that’s more culturally biased.”

And, as minor as it may seem, Wilson-Coles says these little things can trip up a student taking the test.

Stallings also wants the panel to consider equity in technology. The ISTEP+ is currently administered both via paper and pencil and online. The state wants to move to all online testings, but Stallings says if that’s where we are going we need to make sure every school is on the same page.

“If we’re going to require schools use technology we need to make sure they have it in such a way that it’s not disruptive,” Stallings says.

The first meeting convenes in a few weeks, and superintendent Roberts says he is a little worried about the tight timeline. The panel has seven months to have their discussions and issue the report.

Wilson-Coles says she is excited to be a part of the panel because she feels she is speaking for so many teachers who are frustrated with the current ISTEP+ and the high stakes that go with it.

“I hope it gives us a voice and the panel will listen and take heed to it,” she says. “And not just say we’re stopping ISTEP+ and put another test that’s the same thing with a different name.”

DONATE

DONATE

View More Articles

View More Articles

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.