New research shows the life expectancy gap is nearly 17 years between the longest-living and shortest-living zip codes in the Indy metro area.

Where you live in Indianapolis has a significant impact on how long you live. The gap in life expectancy between different zip codes in the Indianapolis metro area is nearly 17 years, according to a new study by Indiana University Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health and SAVI, a community data center based at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis.

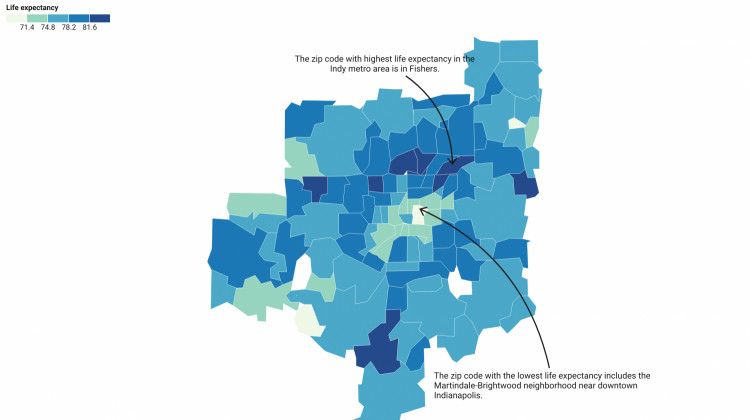

The study looked at 104 zip codes in greater Indianapolis from 2014 to 2018. It found that the gap has widened by 3.2 years since an earlier study with data from 2009 to 2013. Residents of the longest-living communities lived 16.8 years more than those in the shortest-living zip codes in the Indianapolis metro area.

“The gap in life expectancy is just the final manifestation in a series of gaps during living years,” said Tess Weathers, research associate at the IU Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health and the lead researcher.

The zip code 46218 is located a few miles away from the heart of the city and is home to the predominantly Black, low-income neighborhood of Martindale-Brightwood. That zip code has the lowest life expectancy in the metro area of 68 years. Zip code 46037, where the suburb of Fishers is located, has the highest life expectancy at 84.4 years. The distance between the two zip codes is just 17 miles — less than a 20-minute car drive.

For context: According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, Indiana ranks 39th among all states when it comes to life expectancy. Still, the gap between Indiana and the highest-ranked state in the country — California — is far smaller than the gap between the longest-living and the shortest-living zip codes in the Indianapolis metro area. That gap is just 4 years.

On average, life expectancy in Indianapolis metro zip codes decreased by 0.24 years from 2013. But this decrease was not shared equally. In fact, many zip codes — predominantly White with higher income — have gained up to 6.7 years in lifespan. While other zip codes in the urban core — predominantly Black and Brown neighborhoods — lost up to 5.3 years.

This highlights egregious inequities in health, education and environmental quality facing communities of color in Indianapolis.

The study looked at the period before the COVID-19 pandemic and does not reflect the loss of life that affected Americans overall and the disproportionate impact that Black and Brown Americans experienced as a result of the pandemic.

“The same underlying social vulnerabilities that shortened lives during COVID were already shortening lives in the decades before COVID,” Weathers said. “And they will continue to shorten lives in the future unless we take action.”

Lost Life Across Age Groups

While life expectancy is commonly understood as the average number of years lived since birth, it is also measured at different age groups — essentially measuring how long a person is expected to live after they reach a certain age.

“The remarkable thing is that the [life expectancy] gap is persistent along the age spectrum,” Weathers said.

The new study shows that the biggest gap in life expectancy is in fact at the birth. This means that a child born in neighborhoods with a lower life expectancy is likely to live a shorter life than one born in neighborhoods with a higher life expectancy. This gap narrows when a person lives until 55 years of age. And then widens again at age 85.

In other words, babies living in the communities with lower life expectancy are expected to live only 80 percent of the life span of babies living in higher life expectancy neighborhoods. And elders who reach 85 years of age would live only 7 percent of the remaining life that their counterparts in higher life expectancy zip codes live.

Better Education Impacts Life Expectancy

The report looked at the many factors contributing to this gap. Educational attainment seems to be one of the most telling factors in the life expectancy of a population. In Indiana, those who have not completed high school are four times more likely to be in fair or poor health compared to those with college degrees. The study shows that education explains as much as 57 percent of the life expectancy gap.

Researchers believe that is due in part to the cascade effect educational attainment has on a person’s life — education can reduce precarious employment situations and increase the ability to earn a higher income. Another earlier study co-authored by IU researchers showed that being in a precarious employment position negatively affects the health of an individual, especially during environmental or health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Income, Segregation And Quality Of Life

The study also looked at the zip codes with the highest segregation rates. The average life expectancy at birth of those who lived in the most segregated zip codes was 3.9 years less than those in the lesser segregated zip codes.

Historically racist practices like redlining in which residents were denied access to loans and neighborhoods were graded from A to D — A being “best” and D being “hazardous” — led to decades of disinvestment in certain neighborhoods. The grading system was primarily based on race, and neighborhoods with Black residents often received the “hazardous” designation.

The impact of this racist system lives on. Black Americans have less generational wealth, less access to opportunities and live in neighborhoods with lower quality environmental conditions and access to basic services.

“Wherever redlining was high, opportunities is low,” said Matt Nowlin, user experience designer and data analyst with the Polis Center at IUPUI.

He referred to historic maps of redlining and current maps that show the correlation between the racist practice and current neighborhood segregation, economic opportunity and health disparities.

Indianapolis ranks 42 on a list of 114 most segregated cities in the country and the legacy of this segregation is glaring — even more so than in other major metros in the U.S. A study that ranked the 100 largest metros in the country found Indianapolis to be among the worst 10 cities to live as a poor person. A low-income person in Indianapolis lives a shorter life than a low-income person in New York City, Los Angeles and Chicago. The study says that other cities offer better access to necessary services like education, grocery stores, transportation and employment, which partially mitigates the impact of poverty.

For instance, a 2019 study by SAVI showed that 22 percent of Indianapolis residents live in a food desert. Thirty-two percent of Black Hoosiers live in a food desert, as opposed to 17% of White Hoosiers.

“These are social toxins just as deadly and far more entrenched than COVID,” Weathers said.

No Clear Cut Answer

The study does not establish any causative relationship between certain socioeconomic or health factors and life expectancy. But the Indianapolis zip code data revealed in this study clearly points to the fact that where someone lives and their race can be a predictor of their length and quality of life.

Weathers said the community’s focus should shift from longevity and extending people’s lives to bridging the striking gaps in life expectancy within our own backyard.

“We need to stop blaming the people who live in these places. This is a society-produced problem,” Weathers said. “It takes all of us. It must not be something that we just put off.”

Contact reporter Farah Yousry at fyousry@wfyi.org. Follow on Twitter: @Farah_Yousrym.

DONATE

DONATE

View More Articles

View More Articles

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.